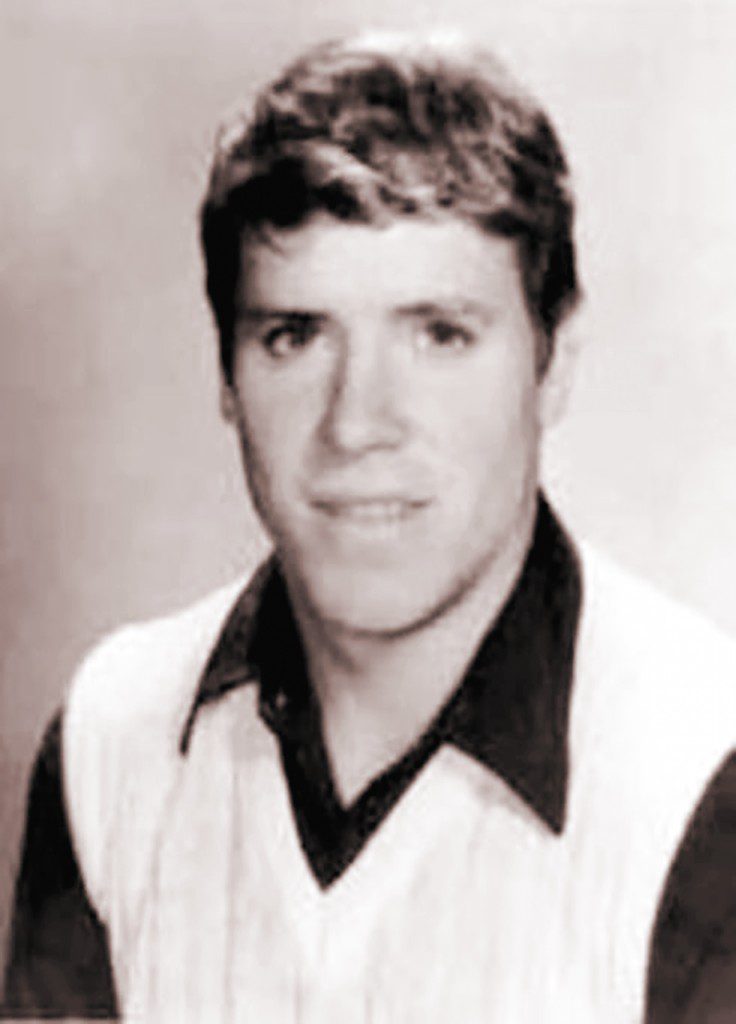

In 1983 Sean Marsee had everything going for him. It was his senior year at Talihina High School, and he was a track star, winner of 28 medals in the sport. He looked forward to the state-level track competition and planned to join the U.S. Army after graduation. Then one day, he opened his mouth and discovered a small sore on the back of his tongue. He waited for the sore to heal, but it didn’t. As it became larger and more painful, he finally confessed to his mother that he had been dipping smokeless tobacco since he was 12 and that he was afraid.

Ten months later, at 19, Sean Marsee was dead.

The Cancer

At the time of Marsee’s death in 1984, nobody was talking about the dangers of smokeless tobacco or “snuff,” as it’s sometimes called. The notion that smoking was dangerous had only recently caught on with much of the public. Nobody gave much thought to dipping. In fact, smokeless tobacco was frequently advertised on television by celebrity athletes like Walt Garrison, running back for the Dallas Cowboys and rodeo star, and the celebrated baseball pitcher Catfish Hunter.

Dr. Carl Hook, however, knew plenty about the effects of snuff. Hook is the CEO of PLICO, a company that insures a large chunk of Oklahoma’s practicing physicians. At the time, however, he was a practicing otorhinolaryngologist at the hospital where Marsee’s mother worked.

“I was aware of the potential for smokeless tobacco to cause ulcerations, dental decay, gum disease and sometimes, unfortunately, cancer formation in the oral cavity,” Hook says. “I treated patients with that type of cancer a great deal during my residency training days at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, particularly at the VA. But all these patients who had oral cancer from using smokeless tobacco…most of them were in their 60s, 70s, 80s. They’d been doing it for years and years. Sean was the youngest patient with cancer from smokeless tobacco I had ever seen.” [pullquote] Sean was the youngest patient with cancer from smokeless tobacco I had ever seen.[/pullquote]

When Betty Marsee brought her son in to see Hook, the physician’s heart sank.

“When he opened his mouth and showed me…I’d seen cancers before, but people were 60 years older than him,” Hook says. “I was not accustomed to seeing that in a teenager. But there wasn’t much doubt in my mind about what it was.”

Hook didn’t even take a biopsy during the first office visit, so sure he was that Marsee had a dangerous malignancy. The surgeon’s training had taught him that in cases such as this – where the tumor could drain into the lymph nodes of the head and neck – removal of the tongue and lymph nodes and a radical neck dissection were usually necessary to stop the spread of the cancer. Marsee, however, was adamant that only his tongue be removed at the time. He knew that if he had any visible surgery to his neck and jaw, he would never pass the physical to enter the military.

“Betty allowed him to make that decision,” Hooks says. “Sean was mature and independent-thinking, and I told him what the recommendation was, and they listened, and he made his decision…She wanted him to get treated, but she wouldn’t force him to do anything he didn’t want to do.”

Betty Marsee was a registered nurse at Valley View Hospital in Ada and the mother of four other children. Marsee’s father had recently passed away, and she divided her time between Ada, where she worked nights and took care of her youngest children, and Talihina, where Marsee and his brother, Shannon Marsee, lived on their own while finishing high school. The family was already close to unraveling under the strain of poverty and, for some members, addiction. Marsee’s diagnosis threatened to send them careening over the edge. His younger brother, Jason Marsee, remembers clearly.

“When [Sean] was doing his first round of chemo, it didn’t seem like it was affecting him at all,” Jason Marsee says. “But he came to me midway through [treatment] and asked me to come with him.”

During the drive to and from Oklahoma City for chemotherapy treatment, Marsee would get so ill that he would pull to the side of the road to vomit and pass out, recalls Jason Marsee.

“We would stay away longer and longer so he could gather himself so no one knew how sick he was getting,” Jason Marsee says. “…He dipped all the way up to his second surgery; he was putting Copenhagen in his mouth when his mouth was nothing but an open sore. That’s the kind of thing we’re dealing with. I found Copenhagen in the dashboard when I dropped him at his chemotherapy. He wrote down, ‘Don’t tell mom, it’s all I’ve got left.’ The addiction where people pull cigarettes out of ashtrays so they can smoke – it’s desperation at that point.”

Marsee’s cancer had metastasized to his lymph nodes, his brain and his back. In a desperate attempt to stop the malignancy’s course, Hook first took Marsee’s tongue. Subsequent surgeries took part of his jaw and the lymph nodes under the jaw. Eventually, Marsee lost most of his bottom jaw, parts of his neck, the lymph nodes under his arms and his pectoral muscles. He had a tracheotomy and received nourishment through a feeding tube. Meanwhile, he practiced with weights to try and train what was left of his neck to hold up the weight of his head. His weight dramatically dropped from an athletic 140 pounds to almost 80.

“He didn’t even look like the same person,” Hook says.

When tentacles of the cancer were found wrapped around his spine and at the base of his brain, Marsee had enough.

“He said no more surgery,” his brother recalls, “and went home to die.”

Marsee’s last picture shows a barely recognizable, disfigured remnant of a boy surrounded by the medals and plaques commemorating his athletic achievements. Shortly after the picture was taken, his journey was over. Marsee died on Feb. 25, 1984.

“I don’t know what happened at the end,” Jason Marsee says. “…I heard a horrific wail, and I knew it was my sister finding him gone. I smiled when it first happened. I woke up thinking, ‘Thank God.’ That wasn’t the case for the rest of my family.”