A giant airport for conventional and hypersonic jets.

A station for bullet trains or hyperloop pods.

Launch pads for satellite delivery and space tourists.

Stands for sky taxis and autonomous ride services.

A subterranean highway with separate lanes for human-driven and autonomous vehicles.

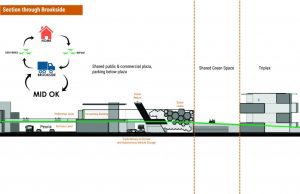

A place called MidOK.

These elements make up part of a transportation hub between Oklahoma City and Tulsa in 2049 that KKT Architects predicts would spawn economic growth, innovation and an eco-friendly environment.

KKT, celebrating its 30th anniversary, created a business-wide project for all 72 employees, whose directions were to envision the next 30 years for the company, especially public-private partnerships involving Oklahoma’s two biggest cities.

“The international airport is the catalyst for everything,” says Francis Wilmore, KKT’s architecture design director. “Both cities would use it and refocus their existing airports for something specific.”

KKT sees the transportation center as an economic engine spurring enormous growth in Oklahoma – akin to what happened in 1974, when the cities of Dallas and Fort Worth unveiled what was then the world’s largest airport. The North Texas region, often called the Metroplex, increased in population from about 2.3 million people to nearly 8 million people in the 45 years since the D/FW Airport opened.

North Texas, the fourth-largest metropolitan area in the country, is one of the top economic drivers in Texas and the Southwest. Revenue from industrial, technological, commercial and residential growth has long eclipsed the $700 million that Dallas and Fort Worth paid for the airport ($3.6 billion in today’s money).

Fort Worth closed its municipal airport, but opened Alliance Airport, an industrial hub, in 1989. Dallas still has Love Field, but its landlocked facilities limit the number of daily flights. (D/FW Airport has about 185,000 daily passengers, Love Field 43,000).

The KKT project was inspired by Tulsa Mayor G.T. Bynum’s 2018 state-of-the-city address, in which he called for cooperation between Tulsa and OKC to solve regional transportation issues.

KKT stresses that its project is merely a concept. The halfway center, dubbed MidOK, does not replace the city of Stroud. The highway does not necessarily replace Interstate 44. However, the firm foresees private investment in a vertical corridor, about 2 miles wide and 90-100 miles long, after the public infrastructure for the transportation hub is established.

The multi-story corridor, with technological, industrial, agricultural, entertainment, educational and residential elements building upward, would allow thousands of acres of land to return to nature.

KKT architect Jim Boulware says the project envisions no one losing property through eminent domain or seeing towns between OKC and Tulsa die.

“Such a project would be hard for Oklahomans to get onboard; we were conscious of that,” he says. “Everyone was sensitive to how a normal, everyday person would react to a giant airport and corridor appearing out of nowhere.”

A transportation hub would require billions of public dollars. A new terminal alone at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport is slated to cost more than $1.3 billion. The Istanbul New Airport, opening in phases with completion by 2025, will cost $13 billion.

However, revenue from jobs created by the MidOK airport and the corridor would far exceed the price tag of the initial public outlay for the transportation hub, KKT says.

Public-private partnerships, according to many economists, make grand visions become reality in efficient, cost-effective ways.

“One of government’s core strengths is that it has the land, it has the assets and it has access to inexpensive money,” Larry Belinsky, who advises municipal governments on infrastructure projects, told governing.com. “I don’t know that people would necessarily think that government’s core strength is building. The private sector tends to be more innovative.”

A tall, dense, narrow corridor of activity between Tulsa and Oklahoma City would change how people live, interact and work, Wilmore says. A hyperloop pod or bullet train would deliver people from both cities to the transportation hub in less than 10 minutes. Hypersonic jets could get a worker with international partners to and from a meeting halfway around the world in about eight hours.

“The idea of commuting to any job completely changes,” says Wilmore, adding that homes and neighborhoods could do without driveways, garages and streets since autonomous ride services would get people to work or play in town or to hyperloop/bullet train stations for out-of-town destinations.

KKT owner Andy Kinslow reminds that everyone, not just those at his firm, needs to consider what the future holds.

“People need to look at where we’re going with technology,” he says. “How do we prepare for it when technology changes?”

Avatars

for the future

As part of the Vision for 2049 project, leaders at KKT Architects created avatars symbolizing people coming in contact with a conceptual hub and corridor between Oklahoma City and Tulsa. Employees from all KKT departments were split and mixed into five groups. Following are glimpses at the avatars and how KKT workers came to envision them as real people in the future.

Gavin

Gavin

Living in Tulsa’s Brookside, Gavin works at the MidOK hub as an autonomous vehicle controller for a regional freight/packaging distributor. Gavin also gets around via autonomous vehicle services, along with high-speed rail and hypersonic transport. He and his neighbors don’t own cars, so their garage-less homes share outdoor areas and meeting spaces.

“The houses face each other and open to a common green space where people mingle,” says Steve Stevens, a relatively new member of KKT’s internet technologies department. “The concept turns the neighborhood around literally and figuratively.”

Wren

Wren

As a chaperone for her daughter’s class field trip to MidOK’s cultural district, the Dallas mother finds everything to entertain a bunch of fifth graders and the supervising adults – several museums, a family-friendly concert and a Broadway show.

Liz Robertson, a KKT interior designer for 11 years, says Wren made team members ask, “What is drawing this person to MidOK? What makes MidOK different from Dallas?”

“We concentrated on Wren’s visit bringing people together and being interactive,” Robertson says, “like an arts center that combines hands-on painting with artificial intelligence or a concert venue where you can experience the performance with people from around the world.”

Robertson says buildings in the cultural district would be flexible so exhibits and programs “would be different every time you come.”

Isaiah

Isaiah

A business traveler with clients and partners in the Middle East, Isaiah maintains his family life daily as an involved father. In the morning, he takes an autonomous vehicle to a high-speed rail station connecting to the MidOK airport, then a hypersonic jet to Dubai for a lunch meeting. He’s back at his Tulsa home for supper with his kids.

All of his travel is in a personal pod that connects to each mode of transport, so he can work while he zooms from place to place.

“We looked at the three speeds of transportation that a worker like him would need – 60-65 mph to the station, 200-plus mph on the train and more than the speed of sound in the plane,” says Jim Geurin, a structural engineer at KKT for 12 years. “Isaiah is a people person; he wants to meet with his business associates one-on-one.

“Thirty years from now might be pushing it for some of what we discussed, but look at what’s happened technologically in the past 30 years. It’s not as far-fetched as you might think.”

Amara and Asher

Amara and Asher

A transportable apartment lets this young, international couple keep a home base in the hub while they easily visit loved ones and have professional trips on other continents.

Amara is a resident at the MidOK university hospital; husband Asher is a graduate student in energy systems and teaches classes at the university.

“With their mobile home, the size of a studio or one-bedroom apartment, they can travel the world,” says Wanas Jasim, a recent Oklahoma State graduate in architecture. “The home would slide into a transportation structure [like a hypersonic cargo jet] and they’d be taken and dropped off anywhere.”

In MidOK, where they live most of the time, Amara and Asher’s home sits on the perimeter of a green berm, which serves as a communal, natural area for them and other residents.

“In the core of the complex, there’s a gathering spot with a lot of water, grass and natural light,” Jasim says.

They live and work on various levels of the corridor, depending upon whether they are at their jobs, traveling to Tulsa or OKC on high-speed rail, or shopping, dining or catching a movie in the hub’s entertainment district.

And when Asher and Amara have children, they can buy a connecting unit that expands their living space and moves around just as easily as their main home.

Joe

Joe

This retired farmer still drives his pickup, built in 2029, the last year manually operated vehicles were made. Joe likes to reminisce with his old buddies every morning at the MidOK Diner, which only serves food produced within a 20-mile radius. He also focuses on what he leaves to his children and grandchildren, particularly with agricultural research and vertical and hydroponic farming.

“We like the idea of moving farming into the future,” says Brandon Hackett, a 13-year architect at KKT. “We came up with a research center where local farmers like Joe can meet with farmers from around the world facing similar situations – like growing corn in Dubai or wheat in Kansas. You can create any type of growing environment at this research center and experiment with what works best. It brings people together.

“We even named the research center after Joe: the Journey Oklahoma Environmental, or JOE, Institute. This was created as his legacy.”

The project’s basics

The project’s basics

Hyperloop transport

Some elements of KKT Architects’ Vision for 2049 are being developed today.

Hyperloop One, part of the Virgin Group conglomerate founded by British entrepreneur Richard Branson, has an operational test facility north of Las Vegas, combines vacuum and magnetic-levitation technologies to propel pods through tubes. Its timeline is for a fully operational system by 2025 with paying passengers onboard in 2029.

The vehicles, designed for 25-28 passengers, have already reached 240 mph at the Nevada site, with a goal of 670 mph. Today’s fastest bullet train, the Shanghai Maglev in China, hits 267 mph, but it doesn’t run in the low-resistance atmosphere of a near-vacuum. Passenger jets travel about 650 mph.

Missouri, Texas, North Carolina, Colorado and a Chicago-Columbus-Pittsburgh consortium have feasibility studies in place. The 250-mile, St. Louis-to-Kansas City route ($30 for the 30-minute ride) would cost between $30 million and $40 million per mile to build, engineering firm Black and Veatch says.

Using similar numbers, a Tulsa-Oklahoma City route, over similar terrain, would cost about $4 billion.

By comparison, estimates for one new terminal at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport run in excess of $1.3 billion.

Virgin is not the only company developing hyperloop technology, but it is the only one with a functional, full-scale track.

Hyperloop One operates in an atmosphere similar to that of being at 200,000 feet elevation. Fans throughout the pressurized tubes create a near-vacuum, which allows a magnetically lifted pod to travel at high speeds with a linear electric motor on what amounts to impulse power.

On July 31, the Indian state of Maharashtra announced it would proceed with a 92-mile, Mumbai-to-Pune route that would open in the late 2020s.

“We’re giving people an option for governments and private investment,” says Ryan Kelly, Hyperloop One’s marketing and communications director.

Hyperloop critics, such as European musician/social commentator Antonio Kowatsch and the American Rail Club, cite safety concerns, unseen energy consumption and disproven technology.

Initially, the fans take a lot of power to pressurize the system, but the energy to maintain the pressure is minimal, Kelly says.

Kelly says a misunderstanding that Hyperloop One operates in an actual vacuum leads to perceptions that people couldn’t breathe should a puncture in a tube or pod occur. A puncture in a tube would slow the pod until the area of the tube could be sealed off and the system repressurized. A puncture in a pod would result in ground-level air coming into the passenger area.

Safety exits would exist every 10 kilometers, or roughly 6.2 miles, Kelly says. Riding in a pod would be similar to jet travel in terms of gravitational forces. Because the tubes are in a closed system, at-grade (or ground) crossings would not exist and would eliminate the No. 1 safety issue involving trains, Kelly says.

Vacuum trains date to the 19th century, but limited technology could not overcome numerous problems. Rocket scientist Robert Goddard designed a system in the 1920s, but it wasn’t fully developed.

In 2012, a hyperloop was proposed by Tesla and SpaceX entrepreneur Elon Musk, who released a white paper the next year. Virgin Hyperloop One expands on all these concepts.

“Hyperloop One exists because of the digital revolution, so pods can ‘talk’ with each other,” Kelly says. “Because it’s an autonomous system, we can have 16,000-plus passengers per hour on one line.”

Kelly sees Oklahoma as a “ripe area for Hyperloop One. We certainly would ask, ‘Do we have public and governmental support and do they understand our mission?’ We need government partners and chambers of commerce to understand our vision to connect metro areas [which] aligns with the vision of the government, such as the creation of jobs, more sustainable jobs and additional trade.

“We’re carrying passengers and cargo. For the Midwest and Plains states, there is potentially more right of way opportunities or partnerships with existing rail lines to get rights of way. From a jobs perspective, we’re a large infrastructure company for welders, engineers and other workers. Layered on top of that are our embedded systems – hardware and software. It’s a nice balance – skill sets that can be converted from traditional jobs and bringing new tech jobs.”

A certification track, which would lead to a global standard for hyperloop systems, needs to be in place before construction can begin on actual lines. Kelly hopes the United States, the European Union, India, several Middle Eastern countries and others will work together to approve this standard by 2024. Routes, such as those in Missouri, India and elsewhere, would be built after that.

“If you look at the United States, everything links by rail to Chicago,” Kelly says. “The same could happen in Oklahoma if they build a transportation hub. If you’re able to travel to the middle of the country from anywhere in the United State within several hours by a hyperloop, that would change how commuting goes and how we get to jobs. It makes a huge difference.”

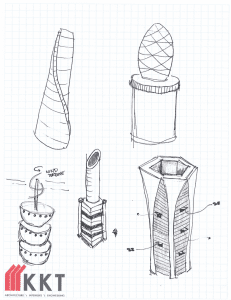

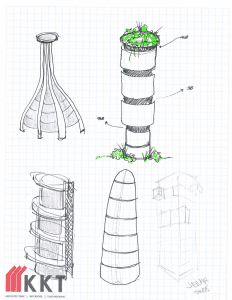

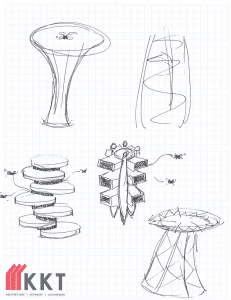

Following are key elements of KKT Architects’ Vision for 2049, a conceptual rendering of a hub and corridor between Tulsa and Oklahoma with transportation, commercial, industrial, residential, agricultural, educational, research and entertainment possibilities. Jim Boulware, a KKT architect for 13 years, says everyone on the five teams assigned to the project “saw the human element at all times and figured out ways to solve problems.”

The site

KKT teams are clear that their imaginary hub is not a substitute for Stroud, halfway between OKC and Tulsa. The corridor and its high-speed rail and highway lanes for autonomous and human-driven vehicles are not necessarily along Interstate 44. “It could be defined by topography and be pretty much a straight line from Oklahoma City and Tulsa,” Boulware says. “It’s not meant to disrupt anyone’s life. We’re not talking eminent domain of anyone’s property.”

Dimensions

The imaginary corridor runs 90-100 miles between the edges of each metropolitan area. It’s about 2 miles wide because it has multiple levels, including several underground. The corridor’s verticality returns tens of thousands of acres of land to nature.

The transportation hub

KKT came up with the name MidOK as the halfway spot between the state capital and T-Town. The project begins at this hub and stretches toward each city with public and private investment along the corridor. MidOK is the center for commerce, transportation, entertainment, industry, research, education and farming. Bullet trains or hyperloops make the commute to MidOK less than 10 minutes from either Tulsa or OKC.

Ground transportation

Highway lanes, with separate lanes for autonomous and human-driven vehicles, are sunken or underground. High-speed rail is on any level – from a subway-type bullet train to pods shooting through vacuum tubes atop columns or pylons several stories above ground.

Aero transportation

In addition to having one of the world’s largest airports, with air and high-speed rail connections to pretty much anywhere on the planet, the MidOK hub has pads and runways for hypersonic jets and rockets. Space tourists and satellite deliveries launch from here. “It provides customizable transportation for each person,” Boulware says. “It’s like a content provider for commuters.”

Commerce

Conference centers, museums, shopping, restaurants, hotels, concert venues and sports facilities, including a stadium for the Super Bowl and Olympics, sprout in the hub and extend toward Tulsa or Oklahoma City. Autonomous vehicles, pods and sky taxis get people from place to place if it’s too far to walk.

Agriculture

Hydroponic and vertical farming provide food for Oklahoma and the world. A research facility draws agronomists from around the world to combat extreme weather and famine. Test facilities simulate growing crops on Mars.

Industry

Manufacturers of all kinds design, build and deliver their products from one place. The hub and corridor create a shipping and receiving mecca for the middle of the continent.

Education

MidOK University offers undergraduate and graduate degrees in hundreds of fields, along with a medical school and residency program.

Housing

People living in apartments, homes and transportable pods connect with each other on multiple levels, literally and personally. Green spaces, natural light, various bodies of water and hundreds of places for daily interaction bring residents together.

Density

The hub and corridor are about “limiting urban sprawl by going vertical and giving the land back to nature,” Boulware says. “With density, you get more people interacting, collaborating and inventing ways to solve problems. That’s how societies advance.”

workplace dynamics

workplace dynamics

KKT’s Vision for 2049 project did not transform the structure of the company and reorganize departments of architects, engineers, interior designers and planners. However, the futuristic concept fostered increased awareness throughout the workplace.

Interior designer Yolanda Wright, with KKT for 29 of its 30 years, was initially hesitant and didn’t buy into why she and her colleagues, all with packed schedules, had to devote many hours to what owner Andy Kinslow calls “a big group project like what you did in college.”

“We’re all busy,” Wright says. “Normally, we keep our heads down and do our individual jobs. But with this pro-ject, we collaborated with all the other disciplines. This led to getting up and seeing what others were doing. It meant getting away from your headphones and music and from concentrating on just what you were doing.”

Wright says getting to know co-workers socially in other departments has been “beneficial to the whole environment” and “made me appreciate what others have to do. For example, human resources and marketing have a lot of deadlines that aren’t commonly known.”

Kinslow says the five teams that fleshed out the futuristic concepts didn’t go in the directions he had anticipated … and he was overjoyed.

“One of our core philosophies is to do whatever you think is best,” he says. “This gives people the freedom to create. I wouldn’t expect them to not do that.”

Kinslow withdrew from team discussions after he and several other leaders offered intentionally vague scenarios.

“I threw the ideas out there and didn’t want them to think, ‘What does Andy want us to do?’ This is not a real project. We just want people thinking,” Kinslow says.

Jim Boulware, a 13-year architect at KKT, says co-workers had always talked with each other about various projects before Vision for 2049, “but now we’re always looking at how to do stuff in the future, not just the present. We’re thinking many decades down the line now.”

Wright adds: “This project has helped us know each other better. At the end, I was really enthusiastic about it. It was a very positive experience.”

Since the project ended, Kinslow has seen co-workers from different departments exchanging ideas and articles about what’s to come.

He acknowledges that the project “wasn’t received well [by some] when it was assigned. After it was over, people were glad we did this. It was a complete attitude change.

“People are thinking down the road. Technology and the future bridge any age gaps or differences.”

The project’s basics

The project’s basics Hyperloop transport

Hyperloop transport workplace dynamics

workplace dynamics