The prevailing expectation for a precocious child who might read early, find simple math easier than the rest of the class and have a voracious appetite for learning is that the student will excel throughout school, go to college and launch a stellar career.

The prevailing expectation for a precocious child who might read early, find simple math easier than the rest of the class and have a voracious appetite for learning is that the student will excel throughout school, go to college and launch a stellar career.

But many parents know that isn’t always true.

Children considered gifted or talented by criteria specified by the Oklahoma State Department of Education have a chance of slipping through the cracks entirely, despite ongoing efforts in education to identify and serve those students.

A 30-year study conducted by researchers at Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College of Education and Human Development concluded that some gifted children face roadblocks to reaching their full potentials in regular public-school classrooms because teachers often focus on underachievers.

Muskogee resident John Fudnil knows how it feels to slip away from getting a quality education, despite showing great promise at a young age. He dropped out of high school and later earned a GED certificate.

“The fact was, I was bored to tears, and honestly I think many of the teachers and the counselor knew it, but there was no alternative at this school,” says Fudnil, who would have graduated in 1989. “If it was a subject that interested me, a 45-minute test would take me 10 minutes and get me scolded for cheating, which I never did.”

Fudnil struggled, not academically, but because he became increasingly absent from and dispassionate about school.

“I was failed my first year in seventh grade – due to attendance – in a vain attempt to get me to go to school,” he says. “I got in a great deal of trouble in school and at home for my attendance, and honestly I was ashamed.”

But Fudnil says he simply found the curriculum an endless stream of uninspiring content that never took him to a higher level – or a high enough level.

And that was that, he says. School wasn’t for him and he left against his parents’ wishes before graduation.

Fudnil says he was a child who “absorbed everything like a sponge” and “skipped into class now and then and aced the exams,” but school officials focused more on his attendance than his accomplishments. He says this warped, cookie-cutter way of thinking from the school’s point of view was the core of the problem.

“You see, I was never broken – the schools were,” he says, “in that they failed to challenge me, failed to identify me, or much worse never asked me why before they wrote me off for not fitting into that old, worn-out mold they’ve been using since the 1930s.”

In contrast, a young man who graduated high school just a few years ago, and who was identified as gifted at a young age, says he wishes he had never been labeled.

Brodey Nelson, of Bellingham, Washington, attended Oklahoma schools beginning in the second grade. He was home-schooled before then.

He immediately bounced up a grade because of his advanced academic abilities, participated in gifted-and-talented programs throughout school, took honors and Advanced Placement courses in high school, and graduated at age 17.

But he doesn’t care a stick for calling kids gifted and talented.

“While some children may need more attention than others, there is a problem with separating into a ‘gifted class,’” he says. “Being told repeatedly that you are a ‘gifted child’ puts these kids (myself included) into a headspace of, ‘I’m naturally talented so I don’t have to try as hard.’”

“While some children may need more attention than others, there is a problem with separating into a ‘gifted class,’” he says. “Being told repeatedly that you are a ‘gifted child’ puts these kids (myself included) into a headspace of, ‘I’m naturally talented so I don’t have to try as hard.’”

He didn’t realize he had developed that attitude until after high school, however.

“I think this leads to self-esteem and motivational problems later in life when you realize, ‘Oh, life isn’t going to be a breeze and I’m not naturally talented.’ I just happened to be good at early academics,” Nelson says. “It’s not a realization that springs on you out of nowhere, but this slow crawl of immediately losing interest in new things once you realize you aren’t immediately good at this.”

Nelson says his solution to meet the needs of all students – exceptional or not – is to eliminate gifted and talented programs entirely and focus on improving what is already in place.

“More funding means higher paid teachers, better supplies, more extracurricular activities,” Nelson says. “All of these things lead to more interaction in the classroom, and a thriving community between students. That will get any kid more excited to learn or even keep their interest.”

Gifted-and-talented education was mandated in Oklahoma in 1981. The law defines students who score in the top 3 percent on any nationally standardized test of intellectual ability as gifted and talented.

Children known to excel in creative thinking, leadership, and visual or performing arts can be labeled gifted and talented, too.

The state provides funding for gifted-and-talented programs – about $45 million a year. School districts, however, decide how they spend that money to support such students.

Cindy Koss, state deputy superintendent for academic affairs and planning, says sometimes teachers are able to differentiate instruction within a certain subject, so gifted students can advance quicker.

“Or perhaps the gifted student is able to do a project related to the topic they are studying,” she says. “There are a variety of ways schools and teachers can differentiate. And there are a variety of programming options. There are many districts that have enrichment classes, often during the school day, sometimes across grade levels. Again, that varies, but the focus is developing critical and creative thinking.”

“Or perhaps the gifted student is able to do a project related to the topic they are studying,” she says. “There are a variety of ways schools and teachers can differentiate. And there are a variety of programming options. There are many districts that have enrichment classes, often during the school day, sometimes across grade levels. Again, that varies, but the focus is developing critical and creative thinking.”

Schools across the state use a variety of programs to serve gifted students, including mentorship programs, seminars, summer and after-school enrichment programs, creative and academic competitions, honors and Advanced Placement courses, and correspondence courses.

But not all gifted-and-talented programs are created equal – largely attributed to funding, which amounts to about $463 per gifted-and-talented student on average.

According to the Oklahoma Department of Education, a small district such as Wagoner Public Schools, with 2,371 enrolled students in kindergarten through 12th grade (with 365 of those students identified as gifted and talented), receives about $134,000 a year.

In much larger districts, such as Tulsa Public Schools with more than 39,500 enrolled and more than 3,900 identified as gifted and talented, that amounts to more than $1.9 million a year.

Talihina Public Schools has 576 students, with 69 identified as gifted and talented. That amounts to $65,836 a year for programs.

The differences between gifted-and-talented programs available in these districts are striking. One district offers after-school programs that include enrichment field trips, robotics, crafts and pre-engineering courses. Another mostly relies on the teachers assigning more challenging work to students in the classroom and offering a robotics club that meets twice a week. Another has a classroom dedicated to gifted-and-talented students with a teacher trained in higher-level curriculum.

Private Schools

Private school is likely the first idea that comes to mind for a parent watching an otherwise bright child fall through the cracks in public school. And for many, it turns out to be the answer.

According to niche.com, which offers a platform for private school students and parents to write reviews and rate their schools, smaller class sizes and self-paced instruction are two reasons private schools seem to be a good fit for gifted students.

In addition, high competitiveness is noted as a strength for most of the reviewers of Oklahoma’s private schools, and most schools report that 95 percent of their graduates attend a four-year college after graduation.

Oklahoma private school tuition costs range from about $6,000 a year to nearly $20,000 a year, and many schools have religious curricula or affiliations.

Most of the schools indicate they offer scholarships for students whose parents can’t afford the tuition, and the Lindsey Nicole Henry Scholarship Act allows students with disabilities to receive funding to attend a private school.

Magnet/Charter Schools

Magnet/Charter Schools

Charter schools, free public schools open to all qualifying students, have to participate in state testing and accountability programs like any other Oklahoma public school.

However, charter schools have a bit more freedom to educate students in innovative ways, or become focus schools for higher-level science and mathematics or fine arts.

For students who find regular public school uninspiring, these schools can be just the environment they need. Each school has an application process with deadlines, some have specific guidelines that applicants must meet to be accepted, and there could be a limited number of seats.

Oklahoma has 30 charter schools, ranging from science academies and college-preparatory schools to virtual academies.

According to the state education department, most charter schools perform well in standardized testing. Among the highest scoring are Dove Science Academy in Oklahoma City and Tulsa, Harding Charter Prep and Harding Fine Arts in Oklahoma City, and the Tulsa School of Arts and Sciences.

Magnet schools are similar, but are generally specialized campuses within districts. For example, Muskogee Public Schools includes Sadler Arts Academy, a high-performing elementary school focusing on dance, music and theater, and Tulsa Public Schools features, among others, Booker T. Washington High School, the Dual Language Academy, Edison Preparatory Middle School and Mayo Demonstration School.

Home Schools

Many parents turn to homeschooling (legal in Oklahoma) by utilizing a variety of educational resources, support groups of other families who home-school, and religious centers.

It can also be a way for parents of gifted children to give their them a more stringent curriculum without exposing them to more mature students and scenarios that skipping grades would provide.

Online resources for homeschooling abound, including complete kindergarten through 12th grade online programs, mail-order curriculum and religion-based curriculum that parents can buy, borrow or rent.

According to the International Center for Home Education Research, about 23,000 children are homeschooled each year in Oklahoma.

The state department of education offers free resources to homeschooling parents at sde.ok.gov.

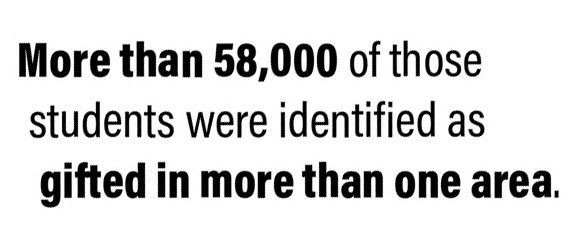

Gifted and Talented Statistics

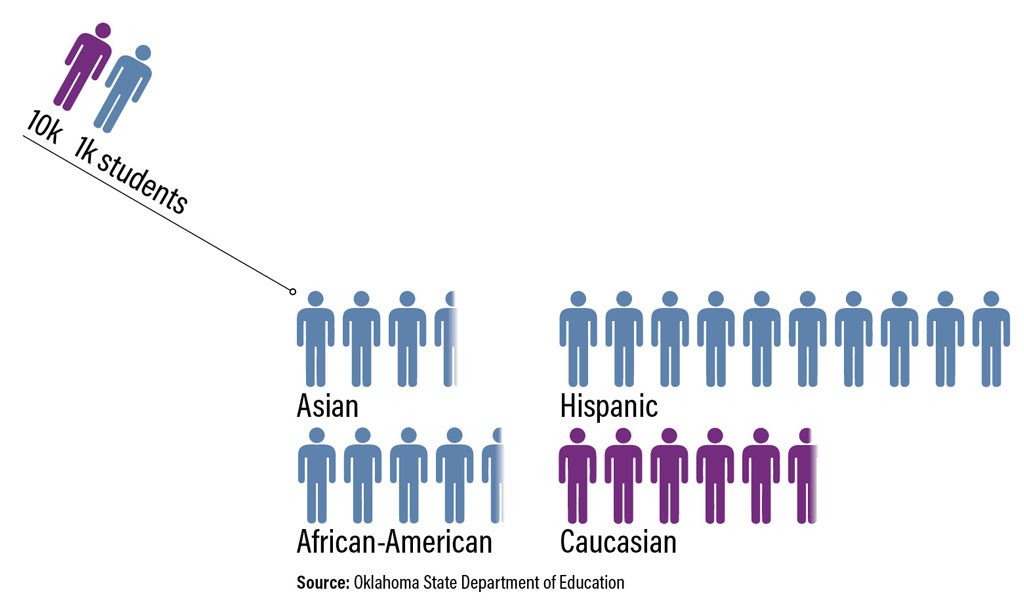

According to the state department of education’s annual report on gifted-and-talented education for fiscal year 2016, more than 96,000 gifted students were identified and served in Oklahoma public schools.

The State’s Public ‘Private’ School

Perhaps one of Oklahoma’s best-kept secrets, the Oklahoma School of Science and Mathematics, is a state-funded school for high school juniors and seniors with exceptional skills in science and math.

Funded by legislation in the 1980s, and free for Oklahoma students accepted to attend, OSSM is a residential school. Students go home to visit for four days, twice a month, but otherwise live in college-style dorms at the Oklahoma City school.

Bill Kuehl, director of admissions, says OSSM offers a collegiate-type classroom experience and university-level curriculum, particularly in science and math.

“You’d have to look in a college catalog to find those courses, and their textbooks are college textbooks,” Kuehl says. “We follow the protocols for graduating from high school in Oklahoma, and the other required courses are rigorous, as well.”

OSSM’s goal, he says, is to create well-rounded students who will get into their first choices of colleges – and begin with a firm foundation.

For students who don’t want to live away from home, Kuehl says eight regional centers offer higher-level courses outside of their regular school days.

“It’s a pretty unique thing,” Kuehl says. “A lot of states don’t even step into this arena. There’s only 10 schools in the country like ours.”