Cities founded by freed slaves are an integral part of Oklahoma’s history.

“There were a number of folks who came to Oklahoma during the land run in 1889 and began boosting Oklahoma as a destination of choice for African-Americans,” says Larry O’Dell with the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Today, only 13 of the approximately 50 original all-black towns remain. Oklahoma used to be home to more of them than anywhere else in the country. They stretched across more than half the state.

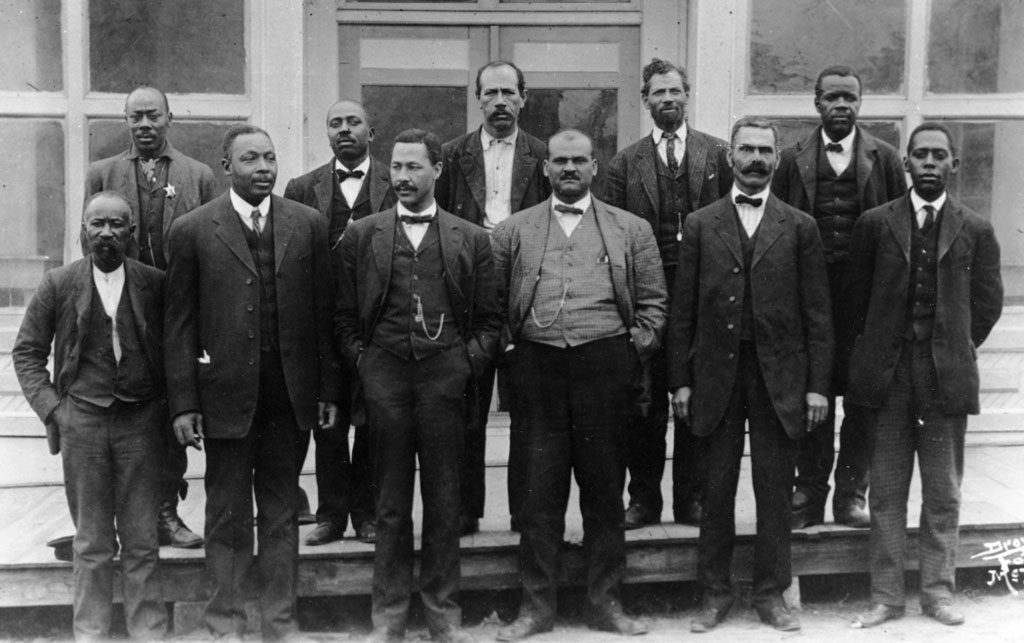

20699.02.197.329 State Museum Collection

O’Dell says when the federal government relocated the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee (Creek) and Seminole nations to present-day Oklahoma, the tribes brought along slaves. During the Civil War, many of the tribes sided with the Confederacy, and their treaties with the government were ultimately annulled. When they renegotiated, the slaves became freedmen and were compensated with land.

“They were treated just like the other members of the tribe when they allotted land to them and broke up their communal living,” O’Dell says. “So, when these freedmen got land, obviously they settled near each other and eventually these towns in eastern Oklahoma developed.”

In Oklahoma Territory, African-Americans from the Old South took part in the April 22, 1889, land run; more than 50,000 settlers raced to a claim a piece of the more than 2 million acres of unassigned land in Indian Territory. Altogether, African-Americans – land run settlers and freedmen – created more than 50 identifiable towns and settlements between 1865 and 1920.

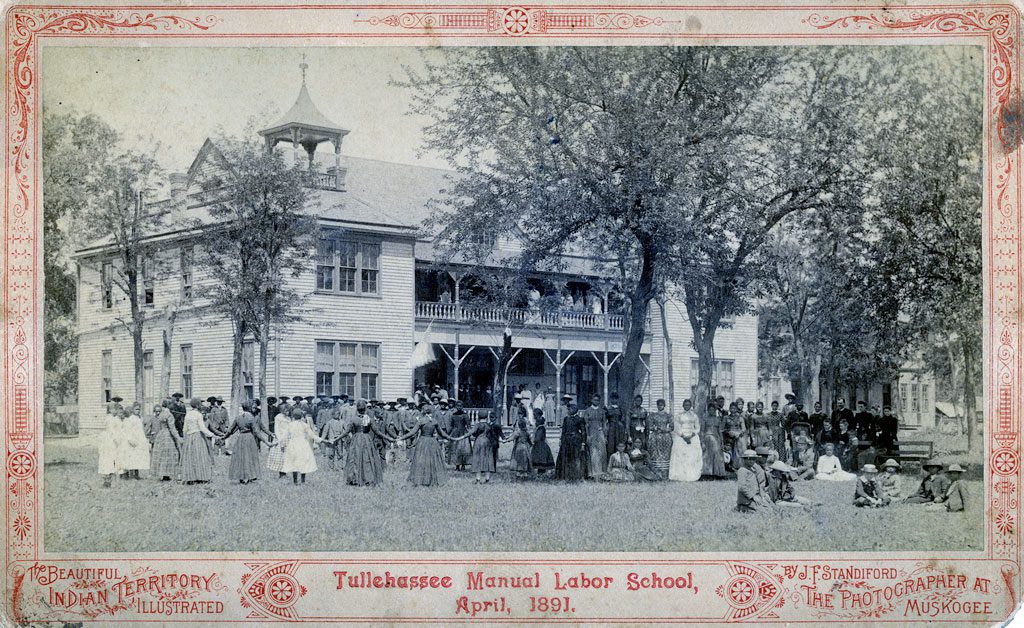

Photo by J.F. Standiford, Muskogee, IT. .1553 Alice Robertson Collection

In these towns, African-Americans lived free from the prejudices and brutality found in other racially mixed communities of the Midwest and the South, O’Dell says.

All-black settlements offered the advantage of residents depending on neighbors for financial assistance and having open markets for crops. According to O’Dell, the all-black towns in Oklahoma were, for the most part, small agricultural centers that gave African-American farmers a market. Prosperity generally depended on cotton and other crops. Men were gainfully employed as farmers or in other types of agriculture, while the women were homemakers and teachers, O’Dell says.

“These towns were the same as any other small town in Oklahoma, with schools, churches and retail,” he says.

According to the Sept. 22, 1921, edition of the Tulsa Daily World, a school in the historically all-black town of Bookertee in northeastern Oklahoma took in about 50 children orphaned by the Tulsa Race Riot.

While Bookertee is no longer a town, nearby Clearview, also a historically all-black town, still exists.

Clearview was once a bustling town of about 618 people, and boasted of the Creek and Seminole Agricultural College northeast of town. In 2010, the population was down to 48.

Lima, located in south central Oklahoma, was one of several towns that had a Rosenwald School – funded by the Julius Rosenwald Fund, which was named for the president of Sears, Roebuck and Company who began the initiative to provide African-American children a better education by funding the first such schools in Alabama.

Boley’s downtown business district is listed in the National Register of Historic Places, and the town of about 1,200 hosts the nation’s oldest African-American community rodeo each Memorial Day weekend.

Pleasant Valley, a settlement in Kingfisher County, was staked by African-Americans in the land run, some of those Civil War veterans.

However, the Great Depression devastated these towns and forced residents to go west and north in search of jobs. These flights from Oklahoma caused a huge population decrease, O’Dell says.

As people left, the tax base withered and put the towns in financial jeopardy. In the 1930s, many railroads failed and isolated small towns in Oklahoma from regional and national markets. As a result, many of the black towns did not survive, but their legacy of economic and political freedom is well remembered.