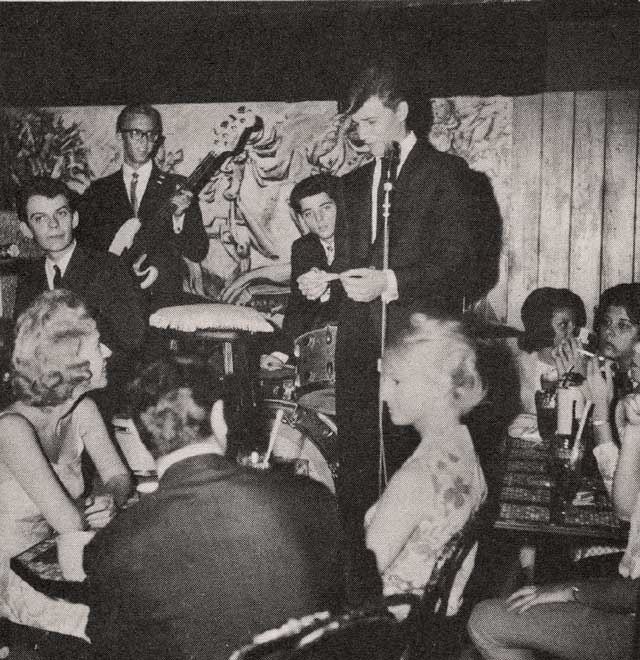

Photos courtesy Jim Karstein and Steve Todoroff

[dropcap]One[/dropcap] of the nicest things about working with author Steve Todoroff on his upcoming biography of Leon Russell, Longhair Music, is that it has given me the excuse to once again talk for the record with my friend Jim Karstein, who, like Leon, was in that first wave of Tulsa rockers to hit the West Coast around the time the ’60s dawned.

By the middle of 1962, Jim held down a steady job as the drummer in a teen nightclub called Pandora’s Box in Los Angeles, playing alongside two other Tulsa boys, Carl Radle and Leon. A few years later, the place would become notorious as the focal point for what were known as the Sunset Strip Riots (which inspired the Buffalo Springfield song “For What It’s Worth”). During the months the Tulsa trio had its gig there, however, Pandora’s Box shone as LA’s brightest in-spot for hip kids.

“It’s mad! It’s gay! It’s elegant! It’s maybe just a little bit expensive … but it’s THE PLACE for teens in search of a glamorous dining and dancing NIGHT CLUB!” enthused an anonymous writer in the January 1963 issue of Teen Life magazine. “It’s tres chic! It’s called PANDORA and it reeks with atmosphere and excitement. From the moment Pandora opened its doors, it became the most popular nightclub in Hollywood.”

A reader of those words back in landlocked Tulsa – or anywhere else – could be forgiven for envisioning Pandora’s Box as a colossal entertainment palace packed to the rafters nightly with young show-biz types and West Coast swingin’ teens. But while it was often packed, it was anything but colossal.

“In Los Angeles, there’s a street that comes up and intersects Sunset Boulevard,” Karstein says. “It’s called Crescent Heights. As you approach Sunset, it forms a Y. In this Y was a little esplanade, an island; now, it’s just a curb filled with chat.

“If we got in the car and drove by that island right now, you’d say, ‘It doesn’t look like there’s enough room on that thing for an outhouse, much less a whole club.’ But that’s where Pandora’s was. There was even actually room for a few cars to park around it.

“I guess at capacity they could get maybe 70 people in there. If they really packed ’em in, standing room only, they might have gotten 80 or 90. But it was a small place, L-shaped, and the bandstand was just a postage stamp in the corner with an upright piano against the wall.”

Leon Russell was the man who pounded that piano, and, with Karstein on drums and Radle on bass, the trio – which Karstein believes was unnamed – worked unceasingly for several months.

“Maybe we played Monday through Saturday and had Sunday off. I don’t remember exactly. I’m sure we played six nights a week, five hours a night.” He laughs. “We used to really work.”

The gig not only entailed playing sets of their own, but also backing all the vocalists booked at the club, many of whom were well-known recording artists.

“We’d do a set, and then maybe Bobby Rydell or Jan and Dean or Dick and Dee Dee would come up and do a set with us,” Karstein says. “Then Preston Epps would come up, and I cannot for the life of me remember what his act was besides sitting there and playing bongos. I don’t know if he chanted or sang. I don’t think he had any band behind him.

“After that, we’d do a little bit more, and maybe Bobby Rydell or whoever would come back and do a few more tunes.”

Epps, best known for his 1959 instrumental hit “Bongo Rock,” had been an original owner of the place, along with actor Tom Ewell. By the time the Tulsa trio arrived on its stage, however, Pandora’s had been taken over by yet another Oklahoman, Enid native Jimmy O’Neill. As a disc jockey, O’Neill had come up through Enid’s KGWA and Oklahoma City’s WKY on his way to becoming what Karstein called “the No. 1 DJ on the No. 1 radio station in Los Angeles, KRLA.” (O’Neill would later become nationally famous as the host of the ABC-TV rock ’n’ roll series Shindig, which featured Tulsan Chuck Blackwell as drummer in its house band, the Shindogs.) And while at least one fan magazine of the time refers to O’Neill as the owner of Pandora’s Box, Karstein believes KRLA may have leased the club as “a big promo deal,” with O’Neill ballyhooing the place on his daily show.

[pullquote]“That’s when rock ’n’ roll was going off like a hydrogen bomb,” he says, “and the Sunset Strip was coming alive.”[/pullquote]

Karstein, Russell and Radle had something to do with all of that, as did O’Neill and another music figure, singer-songwriter Jackie DeShannon, whose long recording career was just getting started.

“Leon was dating Jackie, and Jackie’s closest girlfriend was [songwriter] Sharon Sheeley, who was married to Jimmy O’Neill,” Karstein says. “So the powers-that-be got their heads together and said, ‘Let’s get that Pandora’s Box and turn it into a showcase for Jackie DeShannon.’ Everybody just thought that was a grand idea, and since Jackie was going with Leon, who better to put the band together, right? So Leon gets Carl and me and they’ve got this whole deal planned out – except that Jackie forgot to tell anyone she was having some surgery. That monkey-wrenches the whole deal, so they go to plan B.”

The new tack called for the three transplanted Tulsans to be a house band and, while DeShannon was recuperating, play behind a variety of guest artists. It worked. Pandora’s Box attracted big crowds that included, as the fan magazines reported, some of America’s hottest young stars. Photos in those old publications show TV and movie actors like Clint Eastwood, Johnny Crawford, Shelly Fabares, Lori Martin, Paul Petersen, Connie Stevens, Linda Evans and Tommy Kirk, all living it up at Pandora’s.

“The place could’ve been loaded with movie stars; I’m sure there were a lot of them,” Karstein says. “The only one I really remember was Sal Mineo, who was sitting right beside the stage one night, right at the end of Leon’s piano. On the break I went over and introduced myself. He’d played Gene Krupa in the movie [1959’s The Gene Krupa Story], and Gene was my hero drummer.”

With Radle (who died in 1980) and Russell both gone now, Karstein is the only surviving member of that house band, which made so much noise for those few months in the early ’60s. (O’Neill, another eyewitness, died in 2013.)

“Now you look back and think, ‘Wow, I wish I’d paid more attention to what was going on, who was there,’” Karstein says. “But we didn’t think in those terms then. We had a job. We were in Hollywood. Out there, you could make some money and be where the action was.”

Karstein does remember one other act that played the club regularly, whenever his group was off.

“They sounded like the prototype garage band,” he remembers with a chuckle. “The original No. 1 garage band.”

Some time later, after the Pandora’s Box job was over and Karstein had returned to Tulsa for one of his periodic visits, he called Russell, who’d remained on the West Coast.

“I said, ‘Leon, you remember that band that used to come in and play Pandora’s on the weekends? They were awful. And now they’ve had three hit records!”

“‘I know,’ he said, ‘but that piano player’s a genius.’”

The pianist was Brian Wilson. And the garage band was the Beach Boys.