Teachers of English as a Second Language are all about helping students launch their futures, but it really helps to know where these students have come from, too.

“You’ve got some kids who have had to walk through countries that would just as soon kill them as let them come to the United States,” says educator Cheril Scott, who will retire in May after 16 rewarding years at Capitol Hill High School in Oklahoma City. “But they got here, and they are going to have better lives.”

Barbara McCrary, who spent two years as an English Language Development teacher for Tulsa Public Schools, wanted to see for herself how her Zomi-speaking students had lived in their native Myanmar. In 2017, she visited the country with a group of American teachers.

“I learned what a shock it must have been to come to the United States,” says McCrary. “The first time they wore shoes was to get on the plane to come here.”

She also witnessed “the hard, hard work that children are expected to do. They are taken out to the fields when they are babies. It’s a life of hard labor.”

The Zomi speakers are Christians who belong to the Chin tribe, and are ethnic and religious minorities, says McCrary.

“Their tribe is one that is not favored,” she explains. “Their lives were in danger.”

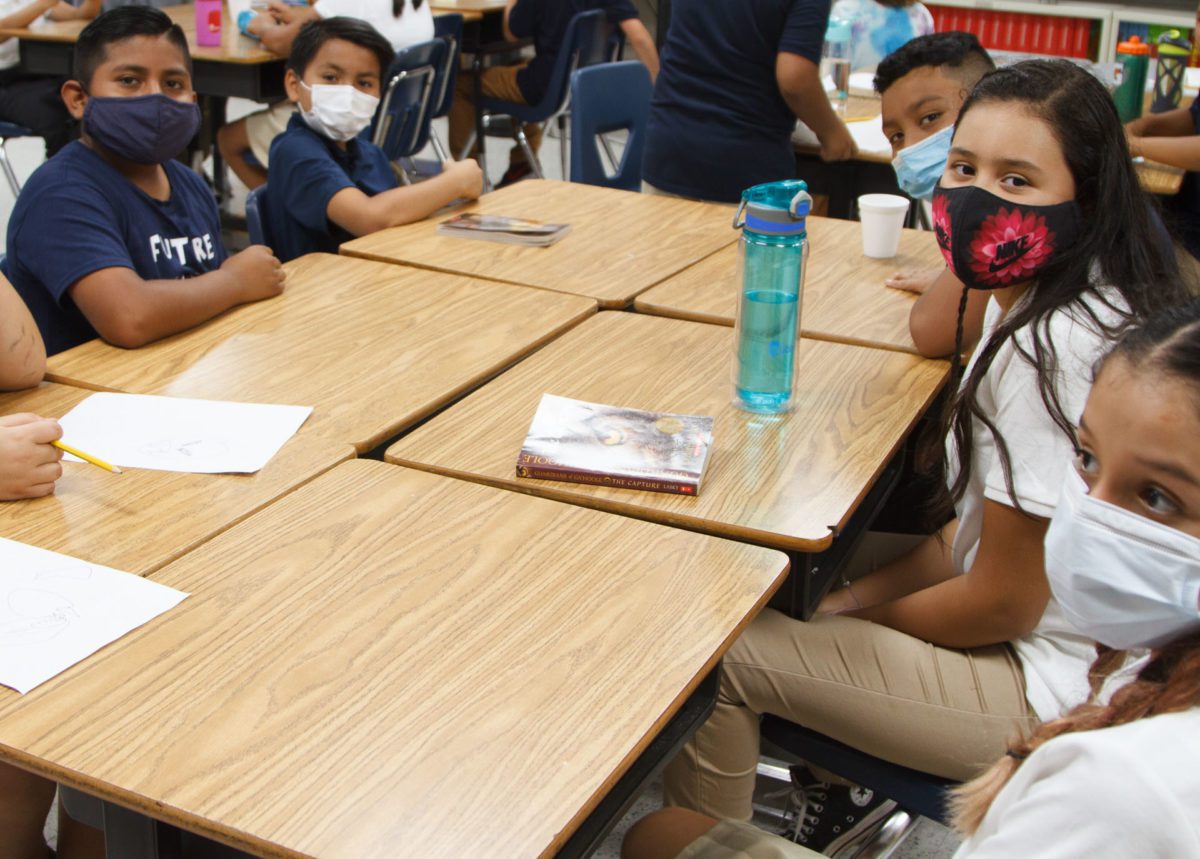

Laura Grisso, executive director of language and cultural services for Tulsa Public Schools, says the district has about 9,300 ELD (English Language Development) learners from 60 countries who speak 72 languages; Spanish is the most common.

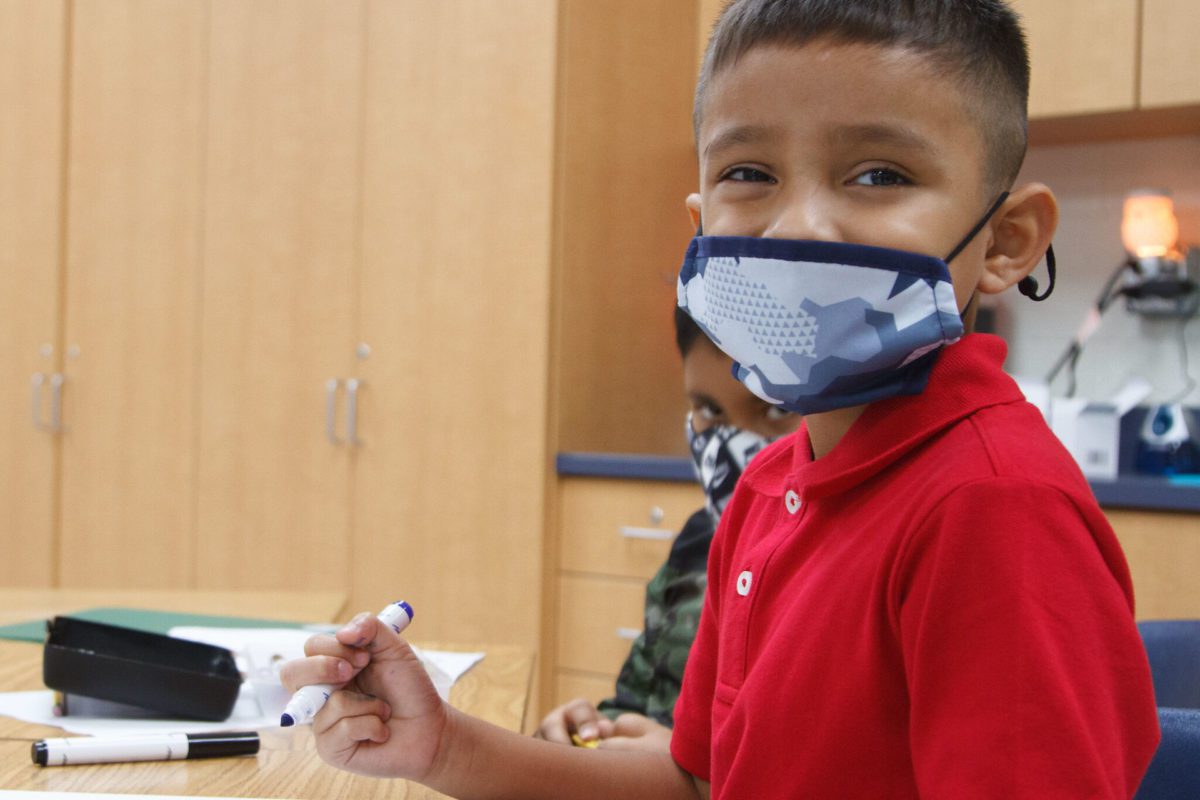

“They are learning English – they are not behind,” says Grisso. “They are amazing kids who come with this wealth of knowledge. They just need to find the words for it.”

Scott agrees.

“They have the exact same capacity as other students, they just don’t have the vocabularies to show it,” she shares. She also says it hasn’t been hard to bond with her students.

“I’ve held their hands through surgical procedures,” she says. “I’ve helped them find a therapist who could understand where they are coming from. I’ve attended quinceañeras.”

McCrary, who now teaches in the gifted and talented program, misses her ELD days.

“I loved that the kids really appreciated education,” she says. “They respected their teachers, and we had great support from the parents. They are eager learners. I still keep in contact with those kids.”

Scott says she is frank with her students about what it will take to train for stable and rewarding careers while still learning a new language.

“We encourage them to go to Rose State College, or Oklahoma City Community College for the first two years, where the class sizes are smaller and the professors are more understanding,” she says.

Grisso says students from Afghanistan are expected in Tulsa schools in the coming months.

“We are very quickly learning about Afghan culture, language and etiquette, and how we [can] help them feel safe, how we [can] help them transition,” says Grisso.

Becoming an ESL Instructor

Teachers with a teaching certificate in any area can apply to be an English Language Development teacher, says Laura Grisso, executive director of language and cultural services for Tulsa Public Schools.

Oklahoma does not require ELD teachers to be certified, but a certification exam is available from the state education department, Grisso says.

Tulsa now asks its ELD teachers to certify by the end of their first year, and the district offers monthly study groups, online test preparation and reimbursement for the $135 testing fee.

The Oklahoma Foundation for Excellence, based in Oklahoma City, launched a program last year offering testing vouchers and an online test prep course, says Grisso.

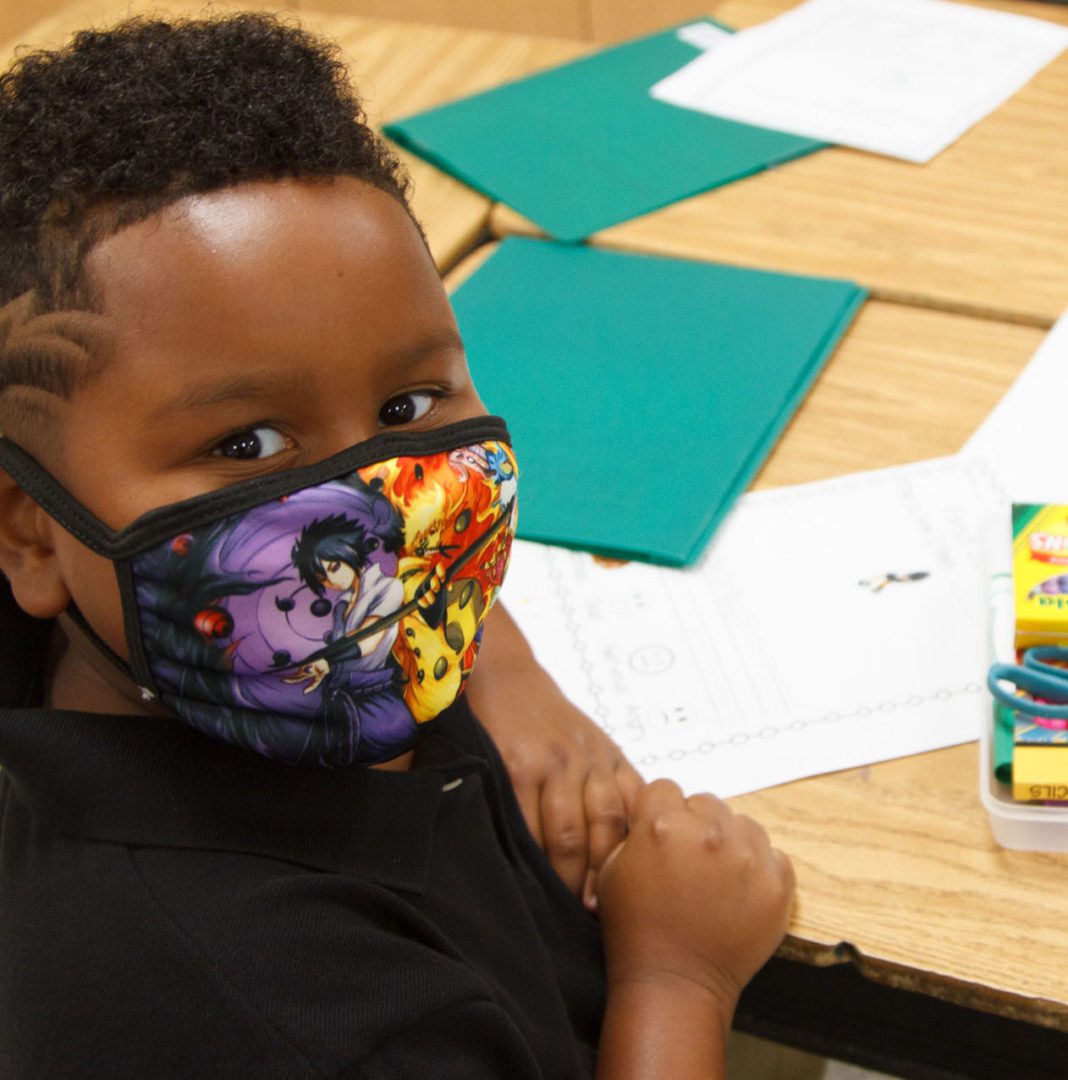

Photos courtesy Tulsa Public Schools