New recruits get hugs and candy bars. Deployed personnel receive ‘Freedom Boxes’ filled with toiletries and Girl Scout cookies. Returning veterans find camaraderie and comfort.

And when it’s time for the final goodbye, grieving families are supported at the service and at the cemetery.

Across Oklahoma, volunteers serve in nonprofits designed to ease the burdens of veterans and active-duty military personnel.

“The military is anything but glorious,” says Saundra Bixler, president of Tulsa’s Oklahoma Chapter One of the Blue Star Mothers.

“It’s hard living,” says Bixler, whose father was a lieutenant-colonel in the U.S. Army. “You have wives trying to manage everything on their own while their husband[s are] deployed. There are parents who don’t know if they will see their children again. And their children change after they go into the military. There are a lot of praying parents in the military.”

When families make a request, deployed personnel can receive a package from the Blue Star Mothers as often as monthly. Every box is different depending on donations, but commonly include razors, hand lotion, first aid supplies, paperback books, magazines and snacks such as beef jerky, candy and trail mix.

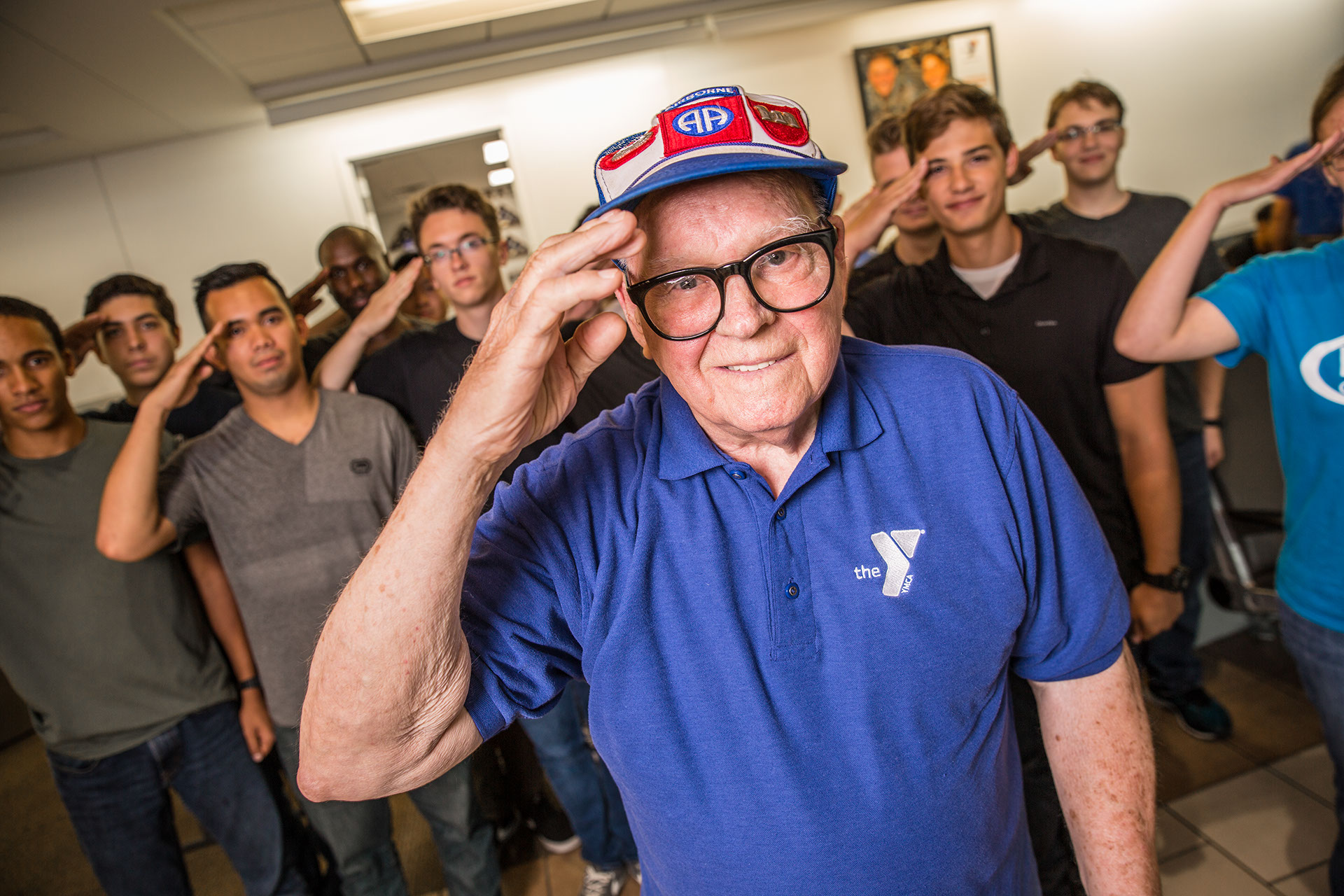

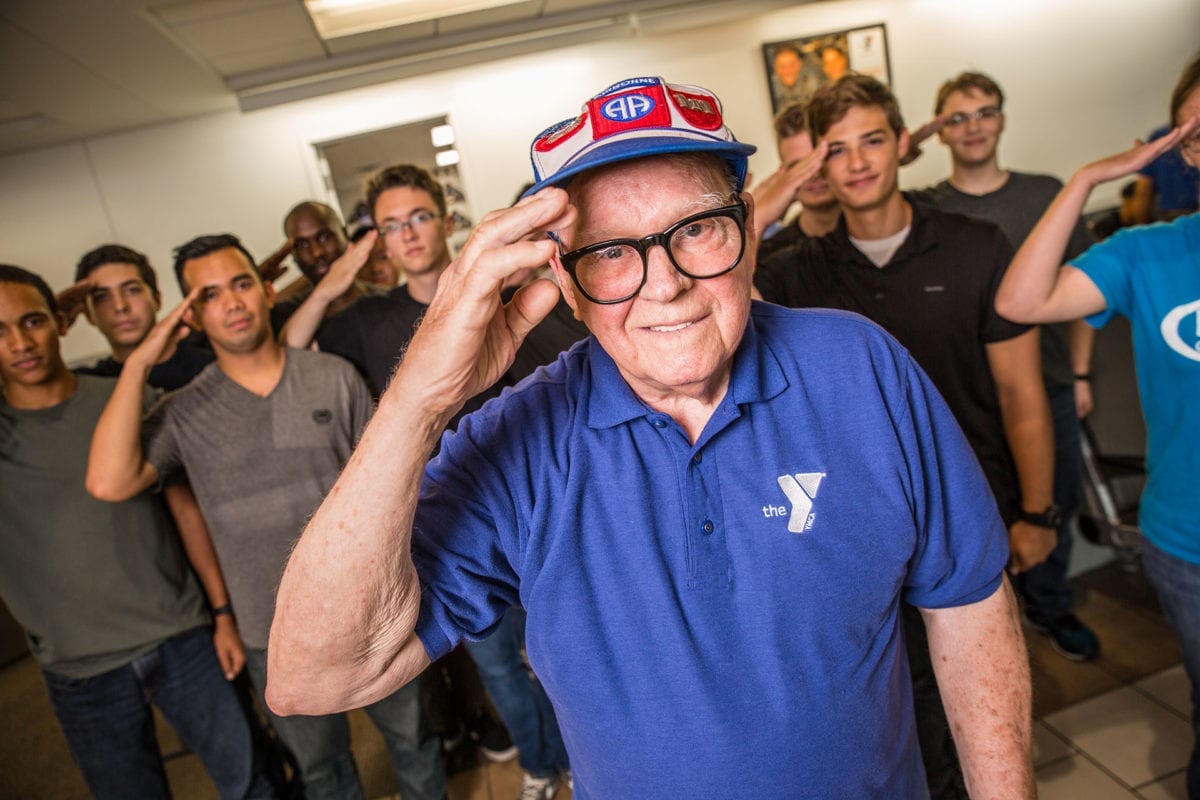

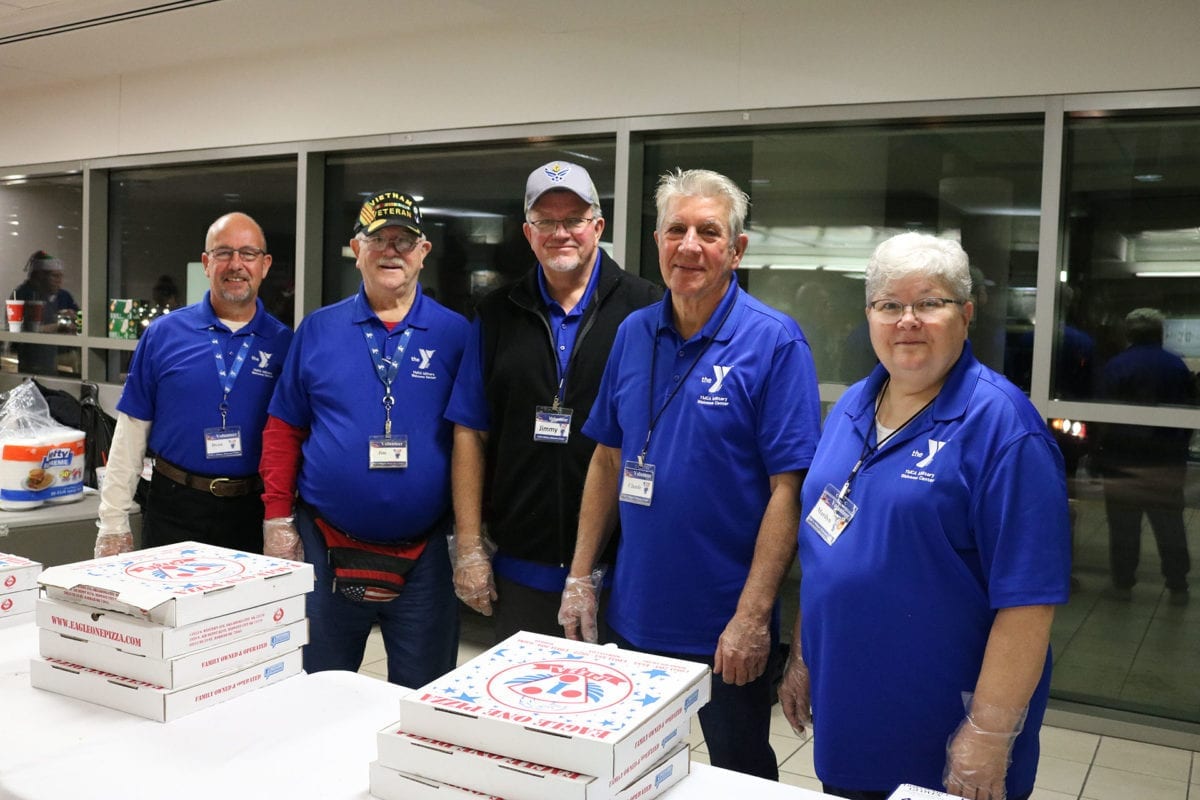

The YMCA Military Welcome Center at Will Rogers World Airport serves active duty and retired military personnel who fly in and out of Oklahoma City and offers special support to Ft. Sill.

U.S. Army recruits headed for basic training come from across the country, says Paul Urquhart, executive director of the Earlywine Park YMCA who also works at the Welcome Center.

“They have just graduated from high school, and for many, it’s the first time they’ve left mom and dad, and even the first time they have flown,” he says. “We take care of them from when they land until they get to Ft. Sill. We feed them, we hug on them, we care for their needs, we provide direction.”

Most of the volunteers are ex-military or had a spouse in the armed services, says Urquhart.

“To me it’s the coolest thing the Y does,” says Urquhart. “Our volunteers are awesome.”

Dan Fuller, commander of Tulsa’s VFW (Veterans of Foreign Wars) Post 577, says that after spending a combined 28 years on active duty and in the National Guard and Reserve, he understands what the post means to veterans.

“It allows you to continue to have the kind of relationships you had on active duty,” says Fuller. “These are people you have a common experience with, that your neighbor won’t understand. A lot of people want to continue the esprit de corps of still serving, still helping.”

The Tulsa post serves breakfast to hundreds of people and enters a float in the parade on Veterans Day, decorates graves on Memorial Day and helps veterans with disability claims. It also partners with the Blue Star Mothers for the Freedom Box project and with the Boy Scouts to properly dispose of American flags.

Cheyenne and Arapaho tribal members are welcomed home from deployments with honor dances, says Cheyenne chief Gordon Yellowman. Typically held during powwows, the dances date back to the days when the tribes had migratory lives on the Great Plains.

“It gives them a sense of pride, and it reminds them of their identity as part of a community,” says Yellowman. “They might have been traumatized while deployed, but that love from their family is healing.”

Lawton nurse and longtime motorcycle rider Cindy Stroud-Ysasaga joined the Patriot Guard Riders shortly after the group was founded in Claremore in 2005. The original purpose was to shield mourners at military funerals from church protestors who claimed the fallen had died defending a nation “awash in sin.”

The protestors have mostly stopped coming, says Stroud-Ysasaga, but the riders continue to provide honor lines and flag lines, when invited, at the funerals of military veterans and first responders.

“We have more in common than just motorcycles,” Stroud-Ysasaga says of the group that now has chapters in all 50 states. “We have unwavering respect for everyone who has risked their lives for American freedom and security.”

When there are protestors to shield the families from, Stroud-Ysasaga says, “we do it strictly by legal and nonviolent means. We don’t acknowledge them. We just protect the families.”

Patriot Riders also build home upgrades for wounded warriors, attend troop sendoffs and place wreaths at national cemeteries. Volunteers who don’t own motorcycles help with charitable projects and drive support vehicles to funerals.

Bixler, whose daughter is a sergeant in the Army National Guard, says anyone is welcome to volunteer with Blue Star Mothers, and mothers and grandmothers of military personnel can be members with voting privileges.

In war zones where troops from across the world are serving, the Freedom Boxes get shared with fellow Americans, soldiers from other countries and civilians, says Bixler.

The Tulsa chapter typically mails 200 boxes a month, but in December, they send as many as 1,000. Students decorate stockings for the well-stuffed holiday boxes, and members of a woodcarving club donate handmade ornaments.

Urquhart says that when his children were growing up, they often went with him to the Military Welcome Center.

“I would credit that as part of why my son joined the Navy,” he says.