This year marks the 100th anniversary of a crimson blot on Tulsa’s, Oklahoma’s, and America’s history – the Tulsa Race Massacre of May 31-June 1, 1921, one of the worst explosions of racial violence the country has ever seen.

Many people outside of our area first became aware of this horrific event only last year, when the HBO alternative-history series The Watchmen began with graphically recreated scenes of violence that had played out in Tulsa’s streets nearly 100 years earlier. And more movies are on the way. Among the announced or proposed projects, most set for release in 2021, are a standalone documentary from CNN Films (in conjunction with LeBron James’ Springhill Entertainment), a documentary series called Terror in Tulsa (with the involvement of another NBA superstar, Russell Westbrook); and a scripted TV miniseries from the Canadian-based Cineflix.

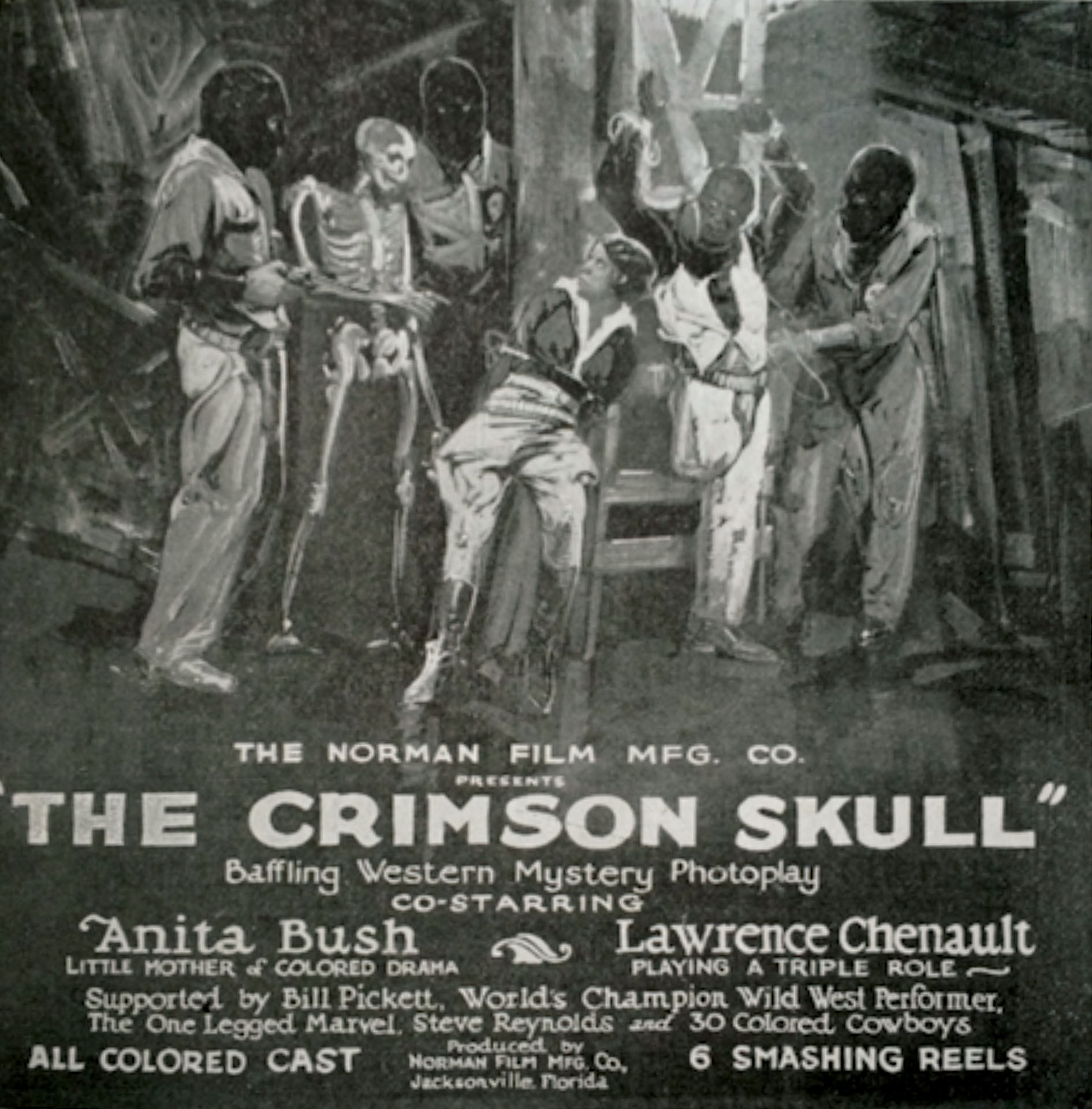

Considering all the movie activity surrounding the centennial of the Tulsa Race Massacre, this might be a good time to look at another film-related 100th anniversary – one that commemorates the first features for Black audiences ever shot in Oklahoma. Those two pictures, The Bull-Dogger and The Crimson Skull, were made during that same year of 1921, and they owe their existence, at least in part, to the scurrilous depictions of African-Americans in the 1915 Civil War epic Birth of A Nation – one of the most technically brilliant and most racist pictures ever made.

Birth of A Nation could be seen as America’s first blockbuster movie, a three-hour-plus feature in which director D. W. Griffith rode herd over thousands of actors and extras and popularized a number of new cinematic techniques, including night photography and montages, that are still in use today. It was a huge hit – and hugely off-putting to Black filmgoers, who desired movies that showed positive images of African-Americans. Soon, dozens of film companies had arisen to serve those audiences, turning out comedies, westerns, dramas, musicals and comedies with all-Black casts, all shown to African-American movie fans in the segregated theaters of the time.

That’s where a white entrepreneur from Florida named Richard E. Norman comes in.

If you’ve read my book on Oklahoma filmmaking, Shot in Oklahoma (University of Oklahoma Press, 2011), you may remember Norman as the filmmaker behind The Wrecker, a 1919 movie shot in Tulsa that starred such personages as Tulsa mayor Charles H. Hubbard, oilman R. M. McFarlin and lawyer/politician M.A. Breckenridge. The Wrecker was what author Barbara Tepa Lupack calls – in her 2014 Indiana University Press book Richard E. Norman & Race Filmmaking – an example of a “home talent” motion picture. Something of a fad in those days, these movies were made by traveling filmmakers like Norman, who would come into a town or city with a script and an offer to make a movie with the locals, giving them the benefit of his time, expertise, stock footage (in the case of The Wrecker, a spectacular train crash), and a finished short film – in exchange for their money. The Wrecker, which ran about 20 minutes, played to packed houses in Tulsa during an August 1919 engagement; versions of the same film were shot in Oklahoma City and many other places across the country, using, essentially, the same script and different actors.

It’s not clear exactly how Norman decided to create his Black-cast pictures The Bull-Dogger and The Crimson Skull in Oklahoma, but the reason surely has to do with a couple of discoveries he made, probably while shooting his home-talent movies here. One was the African-American cowboy Bill Pickett, the man credited with inventing the rodeo sport of bulldogging, who was at the time employed by the famed 101 Ranch around the north-central Oklahoma town of Bliss (now known as Marland). Pickett was a relatively famous performer at the time, thanks to his trick-riding and bulldogging with the touring 101 Ranch Real Wild West Show.

The other Oklahoma factor that must’ve attracted Norman was its all-Black towns, created by freedmen – former slaves of the Five Tribes that had come to Indian Territory. Perhaps the most prosperous of these communities was Boley, an hour or so southwest of Tulsa and a similar distance east from Oklahoma City. To a movie maker creating a film with an all-African-American cast, the potential extras available in an all-Black town must’ve been a real inducement.

In the summer of 1921– only a couple of months and a few dozen miles away from the Tulsa Race Massacre – Richard Norman began shooting footage for The Bull-Dogger, the first of his Oklahoma-lensed pictures. Most of what he initially got was footage from various rodeos, featuring Pickett and other African-American cowboys in competition. Like so many other silent pictures, shot on highly combustible nitrate film, the full-length Bull-Dogger is presumably a lost film; all that we have is about 30 minutes of rodeo footage from the movie. However, a portion of an early shooting script indicates that there was a plot involving Pickett’s onscreen daughter and her beau, who captures a “Mexican desperado” named Manuel Vandalo. Pickett’s daughter was played by Anita Bush, promoted then as “The Little Mother of Colored Drama.” And, while Pickett was certainly a draw for those audience members who knew about his rodeo skills, Bush was the big name in the cast, a renowned New York-based stage and vaudeville artist then with the well-known Lafayette Players at the Lafayette Theater in Harlem.

Bush and Pickett returned – or, actually, probably stayed in Oklahoma – for the second Norman picture, shot in late 1921. The Crimson Skull, filmed entirely in Boley, is an all-out western reminiscent of the Saturday afternoon serials and B-budget westerns that would come along a few years later. While the film is presumed lost, a shooting script (reprinted in Lupack’s book) exists, along with promotional material, which calls it “An Epic of Wild Life and Smoking Revolvers.”

The Crimson Skull revolves around a band of costumed outlaws, The Skull and His Terrors, who are bedeviling the peace-loving town of Boley. Along comes Bob Calem, foreman of the Crown C Ranch (played by Lawrence Chenault, another Lafayette Player and major actor in the early Black-movie scene), who’s in love with the rancher’s daughter (Bush), to try and effect the gang’s capture. In an interesting bit of casting, Boley’s actual sheriff, John Owens, ended up getting the part of the sheriff in the movie – after Richard Norman became concerned, according to author Lupack, about Bill Pickett’s acting ability. (Pickett had been the original choice to play the sheriff; he ended up in a role as a deputy.)

Although Norman planned a third Oklahoma movie, to be shot once again in Boley, he instead returned to his home base of Florida, where he continued making pictures for African-American audiences. A few years later, he did come back to our state for his swan song, an oil field picture shot in Tatums, another Black Oklahoma town. Black Gold was released in 1927 – the same year that Hollywood came out with its first real talkie The Jazz Singer, signaling the end of silent films. The Black film market, which depended upon about 120 African-American theaters along with white movie houses that devoted certain days and/or times to Black pictures and audiences, had never been particularly robust, and with the advent of sound – and the increased cost of making talking pictures – Richard E. Norman retired from the feature-film business.

One hundred years ago, however, during the same year that the heinous Tulsa Race Massacre unfolded, that white Floridian made his own kind of history, creating a couple of escapist pictures for Black audiences an hour away from the site of the massacre that changed Tulsa forever.