[dropcap]Jeff[/dropcap] Reasor works in a world of constant change. The floors shift, the walls move and the ceilings lower, like a clever prehistoric trap in an Indiana Jones movie. The native Oklahoman and CEO of Reasor’s Foods, an independent grocery retailer in northeast Oklahoma, labors in a highly competitive, rapidly changing, often-ruthless industry. But Reasor has managed to take a small chain of grocery outlets started by his father in 1963 and turn it into the 45th largest employee-owned company in the country and the third largest grocery store chain in the state.

“I’ve watched Jeff as he’s moved through the company, starting as the farthest sacker in the back. I’ve seen him move up through the ranks and then take over the company. Jeff is committed to details. He’s committed to looking the process through down to how it affects the customer – all the way down to how an ad reads or how a customer gets through the checkstand,” says Reasor’s Director of Advertising and Branding, Dennis Maxwell.

Reasor learned that work ethic from his father, Larry, who opened a store in Tahlequah, on this premise: Sell the customers what they want, not what you want them to buy. It wasn’t just lip service. It was a prescient exploitation of his major competitor’s weakness.

‘They’re All Our Customers’

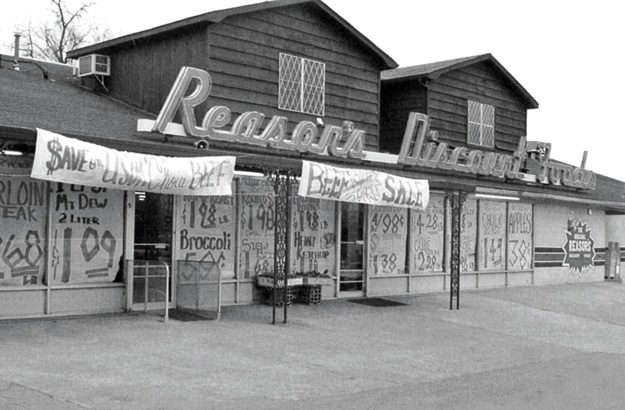

The future CEO rose from humble beginnings, coming from a working class family in Tahlequah. The family vehicle was a 1957 Chevy, and Larry Reasor often drove a three-wheel scooter to work. The first Reasor’s was only 8,000 square feet, a small affair competing against a Safeway on Main Street that had a 35-foot front.

In 1963, Safeway, with two stores in Tahlequah, controlled the local grocery market, much as they did in many other communities. The larger company adopted a policy of pushing its house brands – “private labels” – on customers, dropping mainstream brands.

“They stopped selling the Del Monte green beans and Nabisco crackers and the Keebler cookies,” says Reasor. “Everybody had a sprinkling of private labels, but Safeway, all of a sudden, had four options, and three of them were their products. They trimmed the variety for some of those things people had grown up on.”

That was Larry Reasor’s chance. In 1972, against the advice of friends and colleagues, he opened his second location in Tahlequah, forming the first two links in a chain that would eventually grow to be 19 stores strong.

As a kid, Reasor spent a lot of time in that first store. It was only a few blocks away from the junior high he attended, and he worked there after school, sometimes paid, sometimes unpaid, but always learning.

His first job was sorting pop bottles for return to distributors. Reasor often worked until 8 p.m., when his father closed down the store. It was on one of these evenings, after diligently separating Coca-Cola bottles from the Pepsi and Dr. Pepper bottles, and watching the sun set on the sleepy streets of Tahlequah, that his father taught him that the customer is king.

As his father counted down the tills, preparing for the next day of business, he threw a pile of 20s, 10s and fives in a basket. He turned to his son and said, “Reach in there and grab something.” Confused, Reasor reached in and pulled out a $10 bill.

“Where’d that come from?” Larry Reasor asked his son.

“A customer,” Reasor responded.

“Tell me about the customer.”

“I don’t know. It could have been any of a lot of people shopping here, Dad.”

“That’s it,” said Larry Reasor. “When these people come in, I don’t care if they’ve got mud on their boots, holes in their pants or if it’s one of the guys down at the bank that comes in wearing a suit. You treat every one of them just alike because you don’t know where that money’s coming from, and it doesn’t matter. They’re all our customers.”

Taking Over Business

As Reasor made his way through junior high, he dreamed of being a professional football or baseball player. He didn’t think too much about entering the family business. That came later, in high school – where he established himself as a football star – with college approaching fast.

He entered Northeastern State University on a football scholarship and banged out required courses quickly during his freshman and sophomore years. In his junior year, now thinking seriously about working for his father, he changed up the curriculum, moving into classes about taxes and accounting and swinging emphasis toward business. He left NSU before his senior year to become a full-time Reasor’s employee.

“We hit a growth spurt along in there,” Reasor says. “And people who started [at Reasor’s] after me and who were younger than me were moving ahead of me because football and other college activities kept me pretty busy. I felt like I was going to miss out on some big things. Now, I jokingly tell people that I didn’t graduate from Northeastern, but I did graduate from Larry’s school of hard knocks. If I wasn’t doing things right, I got a lot of one-on-one training, I can tell you that. It was about hustle and determination, but it was also about humility and understanding.”

Reasor’s decision to leave college was a difficult one, but it was the right one for him. The company’s growth spurt resulted in four more stores, expanding the chain into Miami, Langley, Bristow and Owasso. As the company grew, Reasor witnessed firsthand the biggest challenge the business faced and continues to face today – maintaining the company culture, the tone of commerce established by his father in 1963.

“There are a lot of us that have worked our way up, so it’s a family,” says Maxwell. “There’s just an incredible number of people who have been here 20, 25, even 30 years. That just fosters an amazing culture, and there’s a camaraderie here because we have a lot of people who are all working toward the same goal.”

The Company Culture

Larry Reasor never showed his son any favoritism. Reasor says – and his colleagues will back him up – that he worked just as hard, and sometimes harder, than anybody else to get his position. College degree or no, he showed an aptitude for business and honed it every step of the way. And he knew the company culture. After all, he’d been there while his father built it.

Reasor names the maintenance of that culture as one of the company’s biggest adversities and admits that the company still struggles with it, especially as it enters a new round of growing pains with its new store on 41st and Peoria in Tulsa’s Brookside District. But even though Reasor doesn’t know everybody he employs – the number of Reasor’s employees has grown to 3,000 during his tenure – hiring, even at the lowest levels, depends on a candidate’s willingness to embrace the company’s customer-focused culture.

In an effort to reward longtime employees that fostered that culture, Reasor moved the company from family-owned to an employee-owned model in 2007. An idea first broached by his father, Reasor calls it a “glorified 401(k),” in which the asset owned by the employees is the company. For years, Reasor and his father sought a way to give longtime, loyal employees more than a gold watch when they retired. But every time they did, the employees got hammered with taxes. So now there are more manageable financial rewards for longtime employees, but it’s also a matter of passing a legacy to the right people.

Market Changes

“I’m 60 years old,” he says. “I won’t be here forever. I’ve delegated and stepped aside in some areas to allow other people, some within the company and some new, to perform. We’re going through another round of growing pains because of that. The challenge of hiring people and trying to perpetuate what you do well is the most difficult.”

Reasor doesn’t know what the company will look like in 10 years. The grocery market is too volatile to make predictions that far out. He knows there will be new stores, but what they’ll look like is anybody’s guess. Change in market conditions is already reflected in the look, feel and layout of the new Brookside store.

“That store represents a completely different concept than anything we’ve done before. We’re going back now and remodeling some of our stores to look more like that,” says Maxwell.

Market changes are also reflected in the products offered at Reasor’s. Few shoppers, for instance, know that Reasor’s sells more organic produce than any other chain in Oklahoma. And that’s no easy thing to accomplish. The company partners with 50 ranchers and growers, sending out its own people to guarantee not only that the products are organic, but that they’re safe.

“We have more than you think, but we don’t get credit for it,” Reasor explains. “That’s part of the image that we’re going to be working on moving forward.”

Over recent years, the company broadened its selection of products. While people are creatures of habit, says Reasor, they’re also becoming more experimental. Family sizes have shrunk, but those families travel more. When they travel, they find new foods they like and they want access to them at home. Restaurants don’t just serve steak and hamburgers now. He points to sushi, a staple in Reasor’s delis, as an example. If somebody had predicted 50 years ago that grocery stores would offer sushi, Reasor would have stopped going to that somebody for predictions.

But if it’s got to be sushi, then sushi it will be. That’s a fairly predictable reaction from a free-market proponent who, like his father, sees every dollar spent in the store as a vote for this or that product.

“Our thought, and it’s how we ended up with bigger stores, was to put it all out there and let the customer pick and vote,” he says. “Then we’ll pare our mix down to whatever they’re telling us they like. As new items come on the market, we’ll put them out there and give them a fair chance. That’s how we got where we are today.”

Photos courtesy Reasor’s Foods.

There are, of course, challenges that come with that philosophy. Heirloom tomatoes, for instance, are not always perfectly spherical, and they’re not always red. They don’t look like what customers are accustomed to buying, but they taste amazing. Getting customers to try them, leading them to that discovery, is a difficult endeavor.

“We all have our mindsets about things. It’s not a marketing, advertising or public relations thing. It’s just that sometimes Reasor’s hasn’t done the job of telling the story. For instance, I think over time we’re going to try to do a better job of telling people why we use a company called Scissortail Farms in Tulsa. They grow hydroponic, organic lettuce. They’re about five miles from our newest store. We’re selling them exclusively at the Brookside store. There’s a process of telling that story and enlightening people about what we’ve got and where we get it. We’ve got to figure out how to get people over the hump. We’re just trying to provide them with good, fresh, wholesome food,” he says.

Reasor will always be on the lookout for the traps and challenges a capricious market presents. But he will never look away from his working-class roots in Tahlequah, the lessons his father taught him or even the lessons he learned on the football field.