[dropcap]Some[/dropcap] kids go fishing at a river in McCurtain County in 1982.

Acrocanthosaurus atokensis (dubbed “ACRO” by paleontologists) is named the official state dinosaur of Oklahoma in 2005.

The story that lies between these two events belongs in a book, and it’s spawned at least two. The tale of the recovery of the most complete ACRO fossil found to date is riddled with anecdotes, rumors and half-truths, but one thing’s for certain: The addition of a complete cast of the fossil to Idabel’s Museum of the Red River put a small, ethnographic museum in southeastern Oklahoma on the map.

“It’s been a great boon for the museum. It tripled our attendance the first year, and we’ve consistently doubled the attendance since before ACRO,” says Henry Moy, the museum’s Quintus H. Herron Director.

What those kids found in 1982 was a fossilized bone jutting out of the riverbank. They knew they had a fossil of something, but a fossil of what? It stumped local experts. It was eventually sent to the University of Oklahoma, where it was positively identified as ACRO. Word got out.

The Dinosaur No One Wanted

Cephis Hall, a log-cutter and amateur geologist with no college education who resided in Broken Bow, couldn’t believe the news. Hall had been looking for “the big one” all his life. As a kid in school, he didn’t play sports. There was no baseball, basketball or football for him. There were rocks and fossils. They were his thing, and he spent all of his free time collecting them.

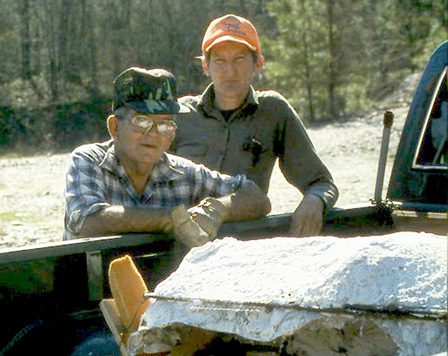

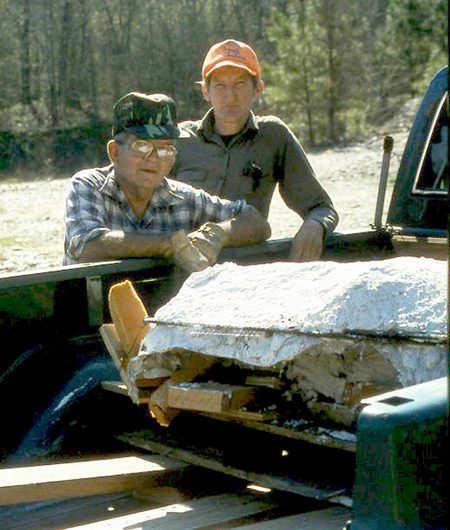

He checked out the site for himself. After a lot of digging, he came up with a leg bone. He brought in his partner, Sid Love, another amateur anthropologist, to take a look. They reached the conclusion that there was more to be found.

“He was just really excited. He couldn’t wait to get back down there and go digging more, and when he found his first bone, he called his partner, Sid Love, in,” recalls Joyce Hall, Cephis’s widow. “They started working on it. They’d cut logs from five in the morning until six in the evening, and then they’d work on the weekends, anytime they could. He just kept after it. He didn’t let up. He kept on until he got the last piece.”

[pullquote]”When he found that skull, and he called one of the professors and told him, ‘Well, Doc, I’ve found that skull,’ the phone just went dead. Cephis thought he’d hung up on him.[/pullquote]They worked on the sly, fearing that amateurs, if they heard about the dig, might want to take a look themselves and contaminate the site. It was crucial to both Hall and Love that ACRO be extracted as professionally as possible, and the techniques they used were those of trained paleontologists. It was done with shovels, picks and equipment occasionally loaned to them by a local company. Professors at OU were aware of the find but showed no interest in committing university resources to the dig.

“No one has ever questioned the quality of work that Cephis and Sid did in terms of the excavation,” says Moy.

They excavated at great personal risk. At one point, they found themselves crawling through a horizontal hole 12 feet under unstable ground. It could have collapsed at any time. But the risk paid off, especially when they found the skull. It was a success that expert paleontologists around the nation had told them they’d never achieve.

The enormity of their undertaking can’t be overstated. Acrocanthosaurus atokensis, meaning “high-spined lizard found in Atoka” (where the first ACRO bones were unearthed in 1940), was the largest carnivorous predator of its time. It was 40 feet long and weighed in at seven tons, slightly smaller than the much younger Tyrannosaurus rex. Some of the bone packets extracted by Hall and Love weighed a half-ton. The excavation took three years, from 1983 to 1986.

“The most exciting thing was that he was told by professors that he would never find the skull,” says Hall. “You’d have to know my husband to know that you don’t say ‘never’ to him. When he found that skull, and he called one of the professors and told him, ‘Well, Doc, I’ve found that skull,’ the phone just went dead. Cephis thought he’d hung up on him. Cephis sent him some Polaroids, and that professor went berserk. That’s the first one ever to be found.”

After a legal battle, won by Hall and Love, with the corporation that owned the land where the bones were found, the fossil found its way to the University of Texas to be prepared. But the university lacked the technology. Building a new lab would cost millions, dollars that the university wasn’t willing to pay. But the school held the bones, unwilling to return them to Hall and Love.