A Theft, And Salvation

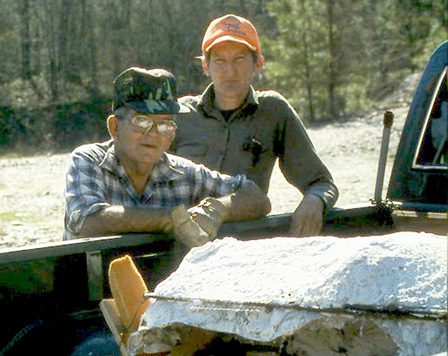

Hall traveled to the university to get his bones back. He was told they’d get to it, eventually. But eventually never happened, and Hall burgled the lab in Austin to remove the bones. The theft set off a dragnet. The Texas Rangers, in cooperation with the Oklahoma State Police, went on a dinosaur hunt. Hall’s house was searched. His son’s house was searched. Other locations were searched. But an army of cops couldn’t find the dinosaur. Hall had taken the bones to Arkansas, where they were held by a distant relative. Eventually, things settled down, ownership was resolved, and Hall and Love had their dinosaur back.

Hall then sent the bones to the Black Hills Institute of Geological Research in Hill City, S.D., the best fossil preparation lab in the country. A series of sales took place, with Hall and Love getting $50,000 for their find. The bones ended up at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, where overeager friends of the museum purchased the bones without doing their research. ACRO had never been traced to North Carolina, but the museum wanted an impressive centerpiece for a new facility. They got one – at a cost of $3 million, the second highest price ever paid for dinosaur bones.

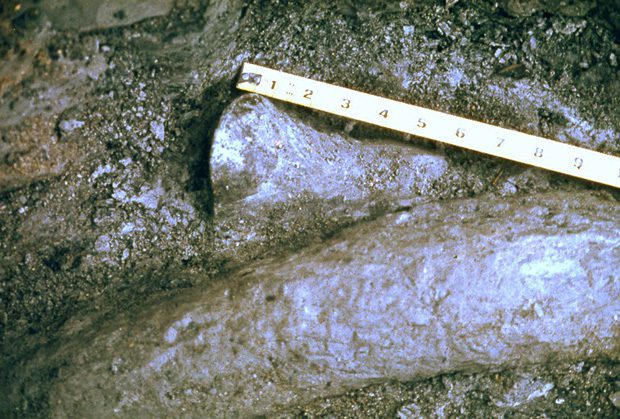

“[The paleontological significance of this find] is that it was the most complete Acrocanthosaurus found to date. It still remains the most complete. It gave us an understanding of the skeleton that was better than what we had,” says Kenneth Carpenter, director of the Utah State University Eastern Prehistoric Museum and author of Acrocanthosaurus: Inside and Out.

Along the way, Hall and Love had been promised a complete cast of ACRO. It was delivered and sat in a barn for two years, unassembled. Meanwhile, the citizens of McCurtain County were getting a bit rowdy. The bones were found in McCurtain County, they said, and should be displayed there. The only exhibiting facility within a 200-mile radius was the Museum of the Red River.

The museum posed to the community a simple challenge. Raise $50,000 and we’ll take care of the rest. The clamor, says Moy, came primarily from local school kids and their teachers. The kids went trick-or-treating with milk cartons with pictures of ACRO on them. Bake sales and cake walks were held. There were rummage sales. School kids collected spare change, and the museum has photos of red wagons full of coins being pulled to the local banks where the hauls could be counted. The coin counters at both local banks were broken by the sheer volume of change. And at the end of the day, with more community donations and matching funds, the kids didn’t raise $50,000; the kids raised $154,000.

The museum lived up to its end of the deal, contributing another $500,000 (and, over the years, more) to erect a building to hold the cast. A team from the Black Hills Institute was brought in to articulate and assemble the cast.

The full story of the McCurtain County ACRO can be found in Russell Ferrell’s Acrocanthosaurus – The Bones of Contention, The True Story of Cephis Hall and Sid love The Arkansas Hillbilly and the Choctaw Indian Who Outsmarted the Corporation and Saved the Dinosaur. Joyce Hall swears to its accuracy.

In 2004, the museum led the charge to have ACRO named the state dinosaur. It was blocked the first year by Norman legislators whose Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History held the official state fossil, Aurophaganax maximus. But in 2005, the legislature passed the measure despite opposition, and ACRO was named the official state dinosaur of Oklahoma.

Today, there are more than 20,000 pieces of art at the Museum of the Red River. Only one is a dinosaur. But it’s a big one, and it’s worth seeing.