What Came Before

Tulsa-based author Clifton Taulbert often poses a question when he lectures about the history of Black Oklahomans.

“How did these people recently freed from enslavement get the mental wherewithal to go out and found towns and universities and start businesses?” Taulbert typically asks his audience.

A primary answer, he says, is that they were “driven by creating a future for their children.”

Many of the more than 4 million formerly enslaved people left the South. The first all-Black town, Nicodemus, Kan., was founded in 1877 and exists today, Taulbert says. By 1901, dozens of Black towns were thriving across Oklahoma.

“Pioneering was the way of life for all Americans about that time period,” he says. “You were always looking for a place to plant your dreams. That did not get lost on their aspirations.”

Langston founder E. P. McCabe was a primary Black towns proponent “and perhaps the most important booster for Oklahoma as an all-Black state,” says Karlos Hill, P.h.D, chairman of the department of African and African-American studies at the University of Oklahoma.

Though McCabe’s proposal “did not come close to happening,” says Hill, “the vision was that it could be a place where Black people could own land, could build businesses, could see in Oklahoma a promised land, could live out their lives to the fullest extent, without racism.”

Tulsa’s Greenwood district was platted in 1906. With statehood in 1907, “it was uniquely positioned to prosper because of legal segregation,” says Taulbert. “They had to open their own businesses because they weren’t always allowed in white businesses. They were ready to build their field of dreams.”

The merchants were making good money, and “all that money was exchanged over and over again in the area of Greenwood known as Black Wall Street,” says Taulbert. An example of such entrepreneurship was Simon Berry, who migrated to Tulsa about 1915.

“He established several profitable transportation businesses at a time when Blacks were banned from using white taxi companies and, of course, train travel was segregated,” says Hill. “He likely was the largest employer in the Greenwood district circa 1921, and maybe even moving forward.”

Some Greenwood pioneers came from Mississippi, says Taulbert, who grew up in the Delta.

“That has always been my pride and joy, to know that many were from Mississippi,” he says. “Berry, who owned the only Black air charter service at the time, was from Grenada, Mississippi.”

Such prosperity led to jealousy, Hill says, which was likely a major factor in the brutal Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921.

“The resentment toward Greenwood can be illustrated by the way in which white Tulsans, and especially the Tulsa Tribune, referred to it in a variety of disparaging ways that ran counter to how the Black community thought of itself,” says Hill. “For whites to talk about it so derisively, and particularly in ways that belittled it, helps us to understand the kind of animosity toward the community.”

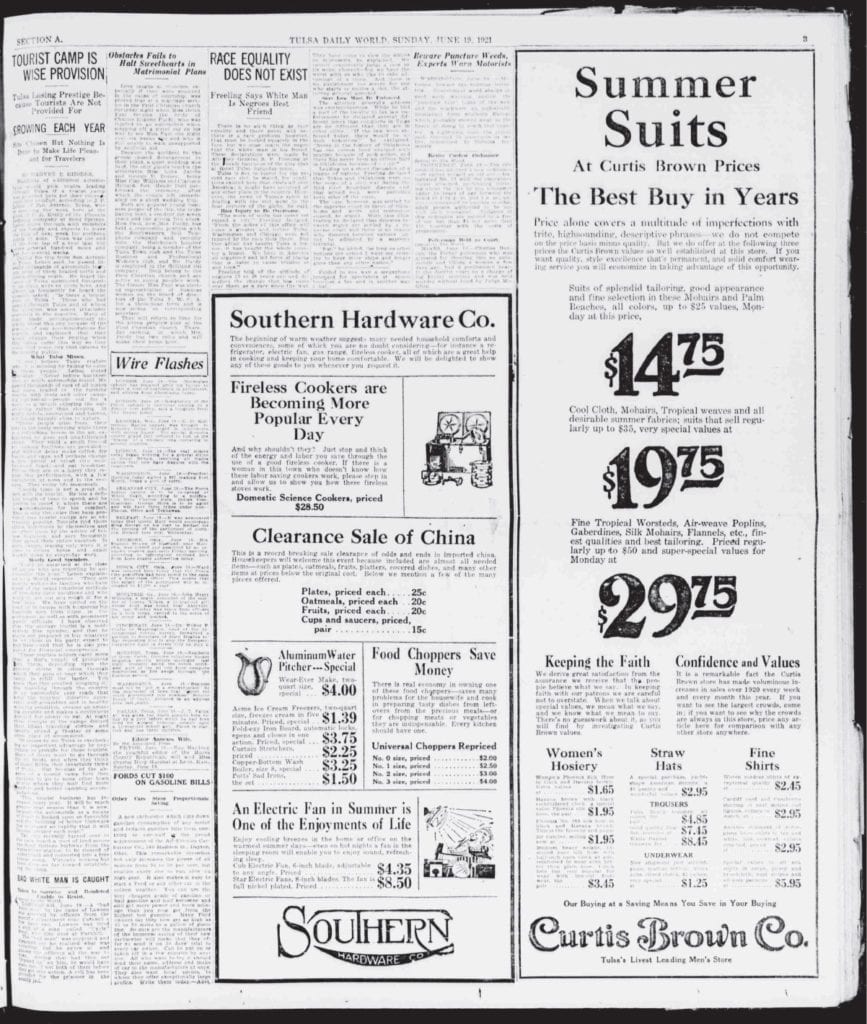

Page from The Morning Tulsa daily world (newspaper). [See LCCN: sn85042345 for catalog record.]. Prepared on behalf of Oklahoma Historical Society.

Page from The Morning Tulsa daily world (newspaper). [See LCCN: sn85042345 for catalog record.]. Prepared on behalf of Oklahoma Historical Society.

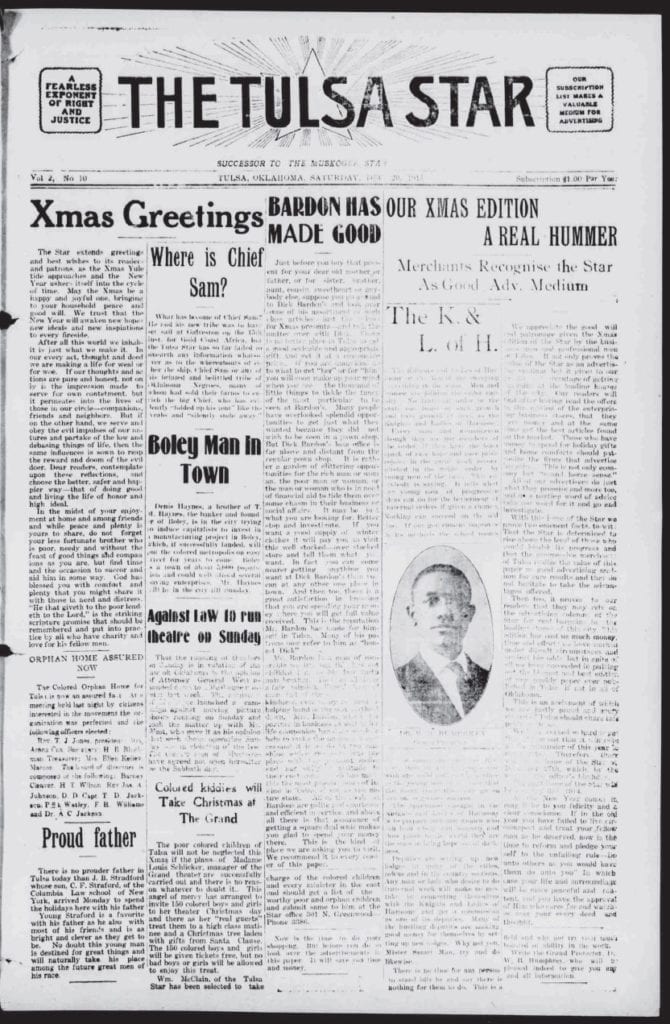

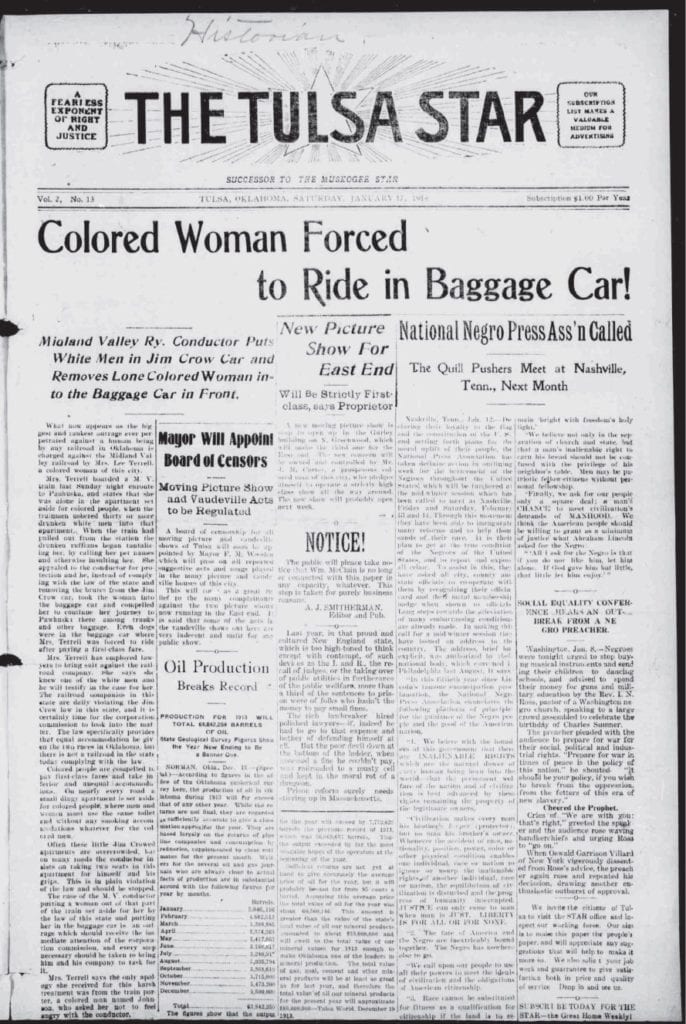

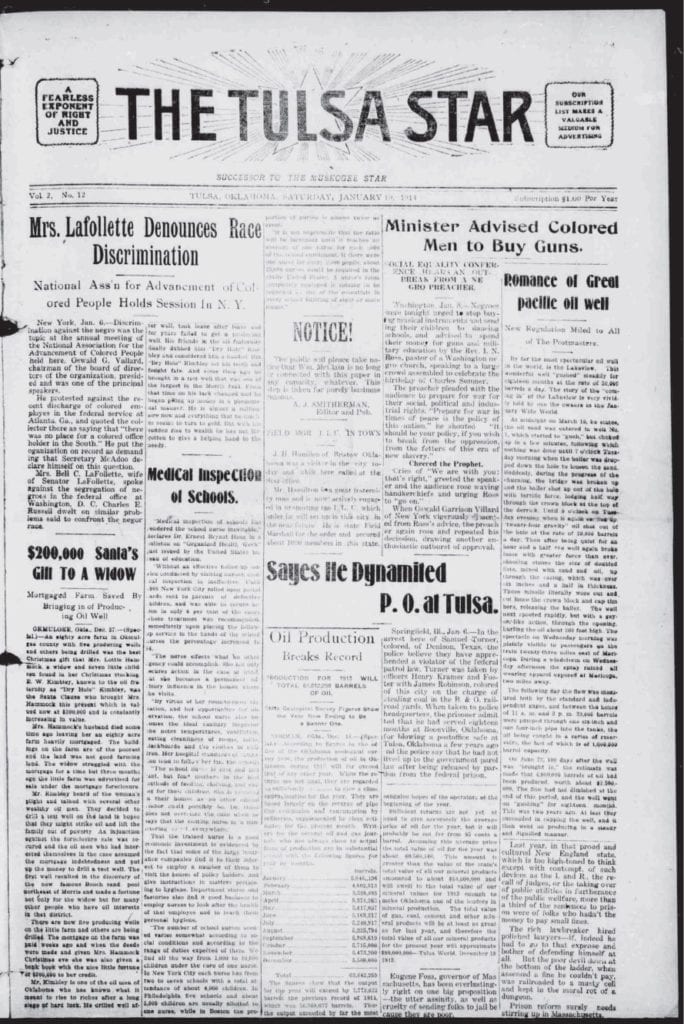

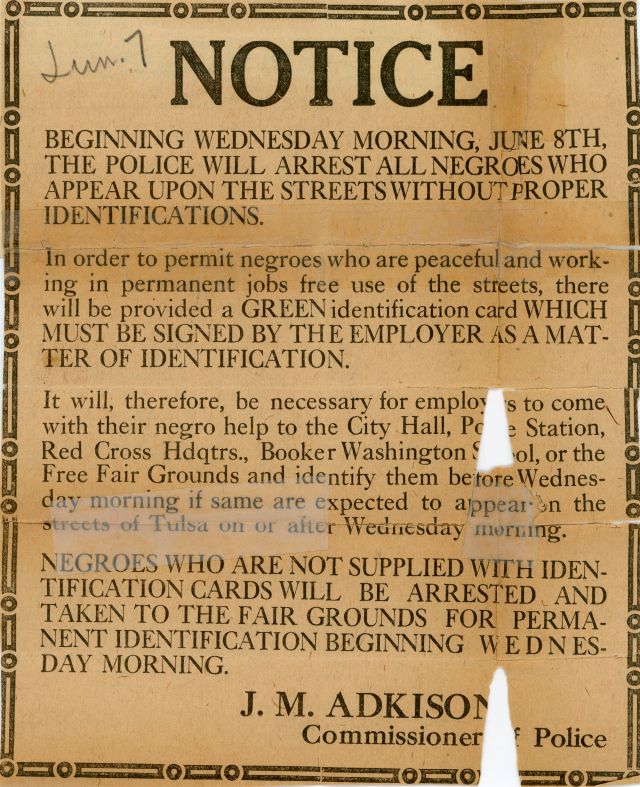

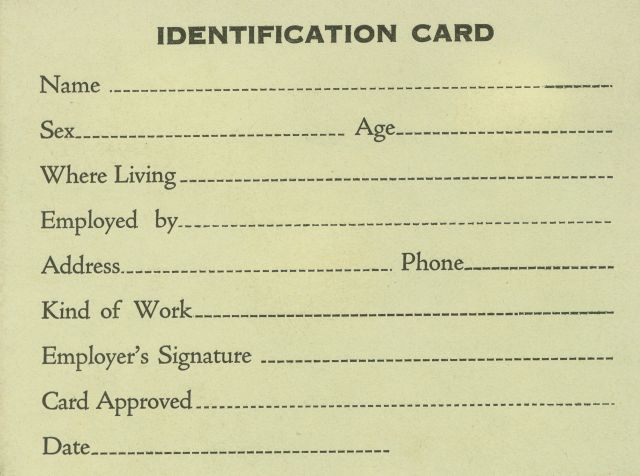

Page from Tulsa star (Tulsa, Okla. : Weekly) (newspaper). [See LCCN: sn86064118 for catalog record.]. Prepared on behalf of Oklahoma Historical Society.

Page from Tulsa star (Tulsa, Okla. : Weekly) (newspaper). [See LCCN: sn86064118 for catalog record.]. Prepared on behalf of Oklahoma Historical Society.

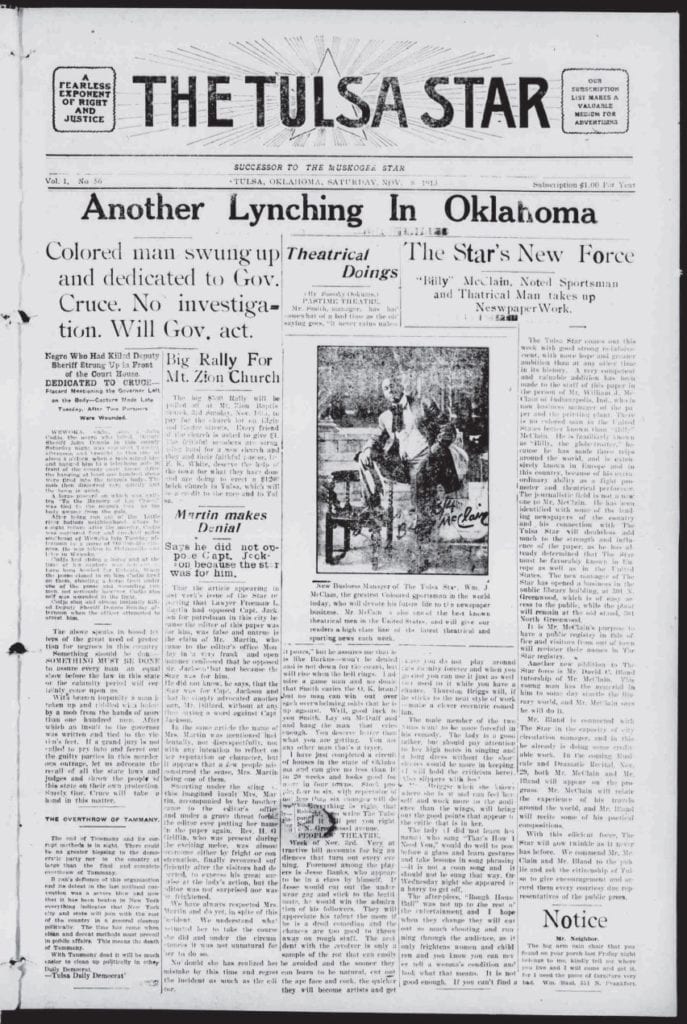

Page from Tulsa star (Tulsa, Okla. : Weekly) (newspaper). [See LCCN: sn86064118 for catalog record.]. Prepared on behalf of Oklahoma Historical Society.

Page from Tulsa star (Tulsa, Okla. : Weekly) (newspaper). [See LCCN: sn86064118 for catalog record.]. Prepared on behalf of Oklahoma Historical Society.

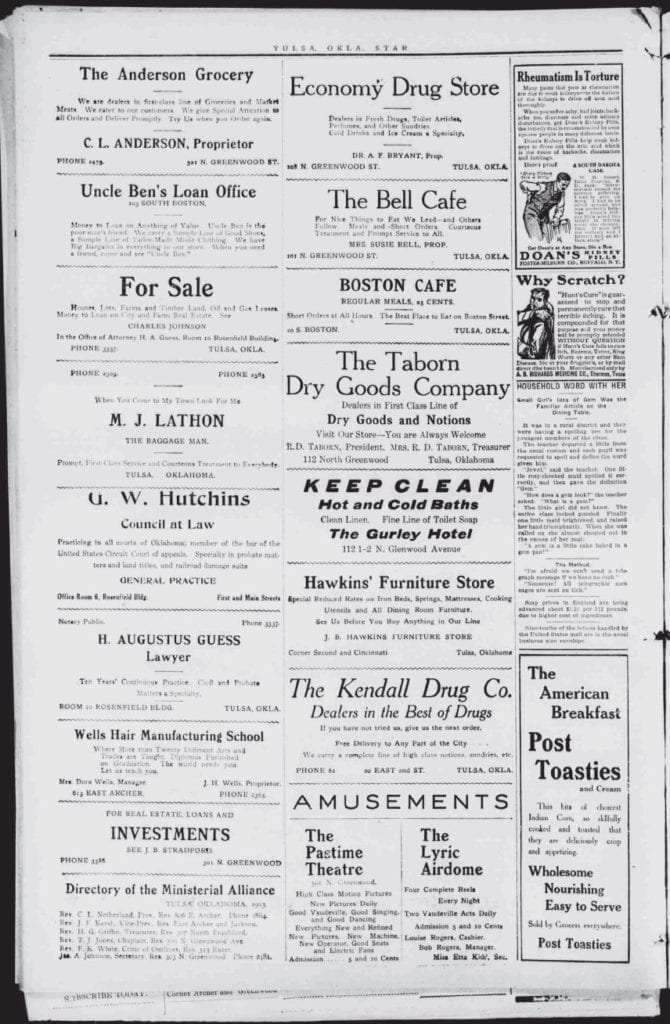

Page from Tulsa star (Tulsa, Okla. : Weekly) (newspaper). [See LCCN: sn86064118 for catalog record.]. Prepared on behalf of Oklahoma Historical Society.

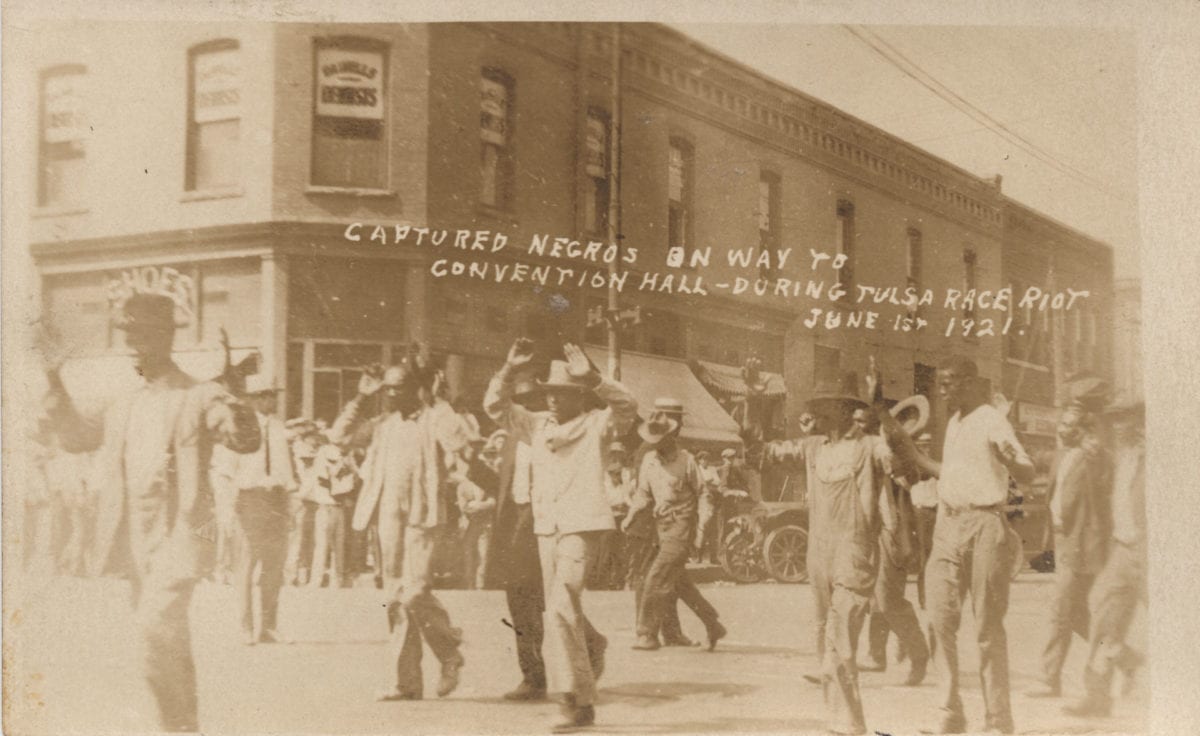

A postcard showing a group of detainees being marched past the corner of 2nd and Main under armed guard. The building in the background is 202 S. Main, on the southwest corner. Based on the shadows of the building and the people, it is late morning. They are heading east (or are turning to head east) on 2nd, so it is more likely that they are among those being marched south towards McNulty Park than to be heading towards the Convention Hall, which is several blocks north of this intersection.

A postcard showing a truck parked in front of the Convention Hall. One man lies on the bed of the truck, either wounded or dead, while two others sit to either side. A man in civilian attire stands guard over them.

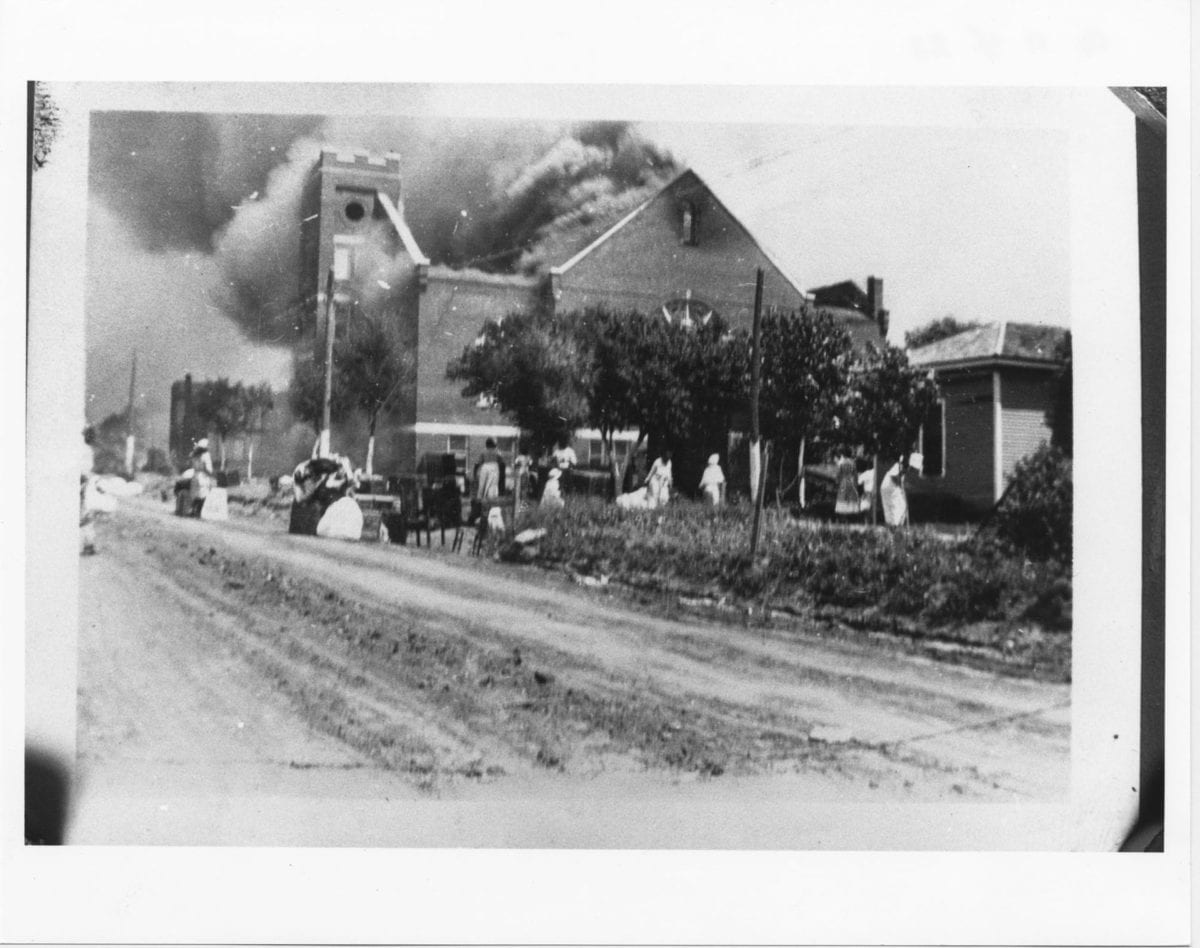

This photographic reproduction shows a crowd looking north up Elgin Ave., watching the Mt. Zion Baptist Church burn.

Photo courtesy the Department of Special Collections, McFarlin Library, The University of Tulsa

The Commission

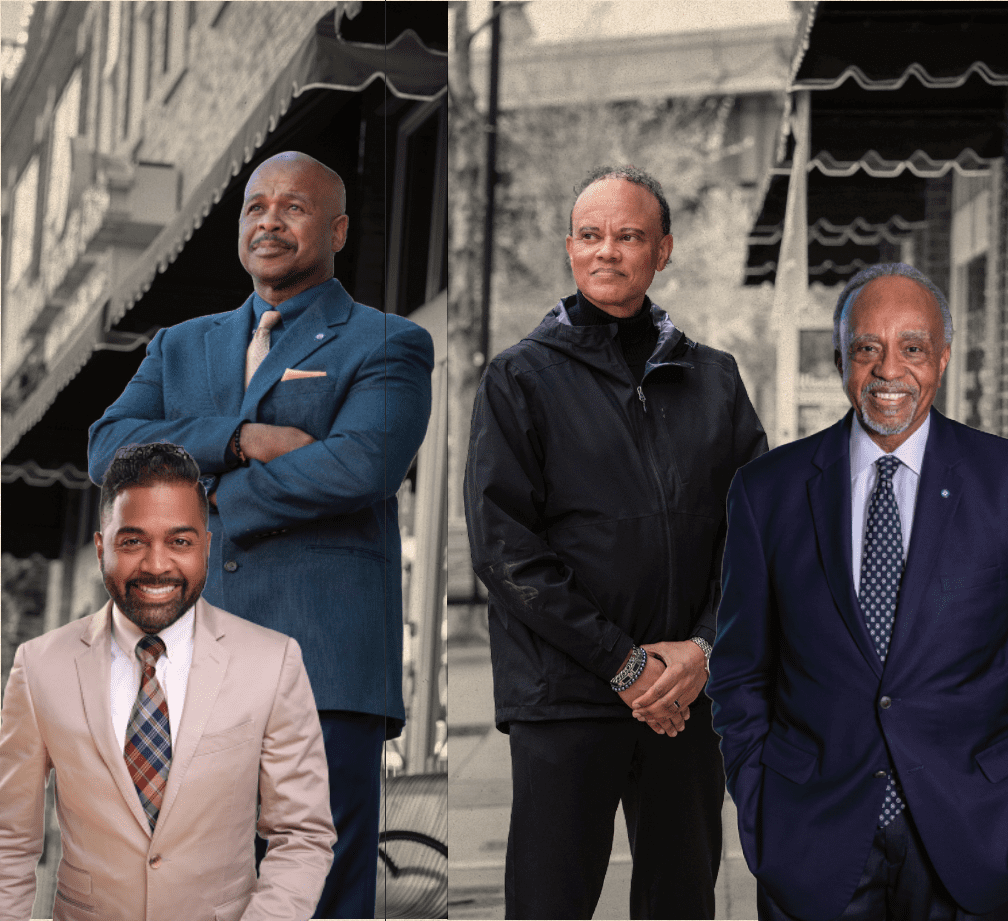

As the centennial of the Tulsa Race Massacre approached, Sen. Kevin Matthews was ready to listen.

“I went to the Greenwood Cultural Center and asked what they needed,” says the District 11 state senator, who also lives in Greenwood.

He was told that the cultural center needed some renovation work. That conversation, along with Matthews’ visit to the National African-American Museum of History and Culture in Washington, D.C., led to his 2017 senate bill granting initial funding and the formation of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, of which he is the chair.

Led by project coordinator Phil Armstrong, the commission has been responsible for the new history center, Greenwood Rising, as well as the observance that started a year before the actual centennial date and will culminate this month and next.

The commission’s mission is to “leverage the rich history surrounding the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre by facilitating actions, activities and events that commemorate and educate all citizens,” according to its website. Apart from Matthews and Armstrong, the group includes 24 commissioners, including Gov. Kevin Stitt and Mayor G.T. Bynum, as well as sub-committees in arts and culture; economic development; tourism; education; reconciliation; and marketing/public relations.

Planning during a pandemic has not been easy, says Matthews, but organizers expect most, if not all, of the upcoming activities to be presented in a live format.

Scheduled events include the dedication of historic Greenwood landmarks on May 22; the John Hope Franklin National Symposium on May 26-29; a Faith Still Standing Unity Day on May 30; and the centennial commemorative program with keynote speakers and candlelight vigil on May 31.

An economic empowerment conference is planned for June 1; the Greenwood Rising dedication on June 2; a global online history lesson on the story of Greenwood on June 3; a Greenwood Film Festival on June 4; and a Black Wall Street Memorial Run on June 5.

More information on centennial events is available at tulsa2021.org.

Armstrong says his goal for the centennial observance is that people “will learn how vibrant and wonderful this community was back in the 1920s, and that we are still reaping the benefits of it today.”

Current photos by Stephanie Phillips; historical photos courtesy the University of Tulsa

A New Way Center

Mental health services

918-599-7277

anewwaycenter.com

Black Wall Street Gallery

Art gallery

918-986-2135

bwsgallery.com

Black Wall Street Liquid Lounge

Coffee shop

539-867-2477

bwsll.com

Big A Bail Bond Co.

Bail bonds service

918-428-6169

Blow Out Hair Studio

Beauty salon

918-576-6200

Blu Print Studio

Fitness center

918-986-2804

thebluprintstudio.com

Cheyenne’s Boxing Gym

Gym

918-808-6320

boxing-with-cheyenne.business.site

Dynamite Cleaning Services

Cleaning service

918-946-3559

facebook.com/dynamitecs

Fat Guy’s Burger Bar

Restaurant

918-794-7782

fatguysburgers.com

Frios Gourmet Pops

Dessert shop

918-949-9879

friospops.com

Greenwood Chamber of Commerce

Historical landmark

918-585-2084

historictulsagreenwoodchamber.org

Greenwood Cultural Center

History museum

918-596-1020

greenwoodculturalcenter.com

Hannibal B. Johnson, Esq.

Attorney/consultant

918-585-6770

hannibalbjohnson.com

King Architectural Solutions

Architect

918-794-0758

kingarchitecturalsolutions.com

The Loc Shop

Hair salon

918-955-2110

thelocshopbws.com

Modern Woodmen of America

Insurance agency

918-884-7474

modernwoodmen.org

Natural Health Clinic

Medical clinic

918-587-4500

nhgreenwood.com

The Pillar Group

Insurance agency

918-392-5665

tpginsandwealthmgt.com

Rose Tax Solutions

Tax consultant

855-818-2937

rosetaxsolutions.com

Silhouette Sneakers and Art

Shoe store

918-732-9166

silhouettetulsa.com

Suited for Life

Non-profit

918-636-0064

suitedforlife.org

Tee’s Barber Shop

Hair salon

918-584-1189

tees-barber-shop.edan.io

Tierre’s Jewelry and Company

Jewelry store

918-645-5326

tierresjewelryandcompanyllc.com

Vicky B’s Dance Co.

918- 928-9500

vickybs.com

Wanda J’s Next Generation

Restaurant

918-861-4142

wandajs.com

100 Black Men of Tulsa

Community organization

918-954-3690

100blackmentulsa.org