It sounds like something straight out of a Marx Brothers movie.

Hundreds of Oklahoma farmers, American Indians and African Americans, armed with shotguns and pitchforks, planned a walk to Washington, D.C., to protest President Woodrow Wilson’s enactment of the draft and plan to enter World War I. Protestors planned to sustain themselves during the march by living off the land, including eating green corn.

For a week in August 1917, southeast Oklahoma lived in terror as armies of citizens roamed the countryside putting down the Green Corn Rebellion.

It was a very different Oklahoma prior to World War I as Nigel Sellars’ The IWW and the Green Corn Rebellion illustrates in the spring 1999 issue of the Chronicles of Oklahoma.

The majority of the state’s agricultural sector was poor tenant farmers raising cotton. Land prices had shot up by 246 percent from 1900 to 1915. Most farmers could no longer afford their own farms. Many sold out and ended up working the land they had owned. The crop lien system and merchant credit between harvests kept tenant farmers in debt to their landlords.

The Oklahoma Socialist Party proclaimed they would expand public lands for tenant use and initiate a cooperative marketing system. At a Sallisaw convention, many also joined the Working Class Union under the leadership of Rube Munson and Homer Spence.

When the 1916 presidential election took place, Socialist Party presidential candidate Allan Benson won 15 percent of Oklahoma’s vote while winning only three percent nationally. The Socialists won 25 percent of Seminole County and 22 percent of the vote in neighboring Pontotoc County.

Falling cotton prices had heightened tensions in southeast Oklahoma. Dewar’s water tanks were dynamited, there was a gas explosion at Kusa and Henryetta’s sewer mains were sabotaged.

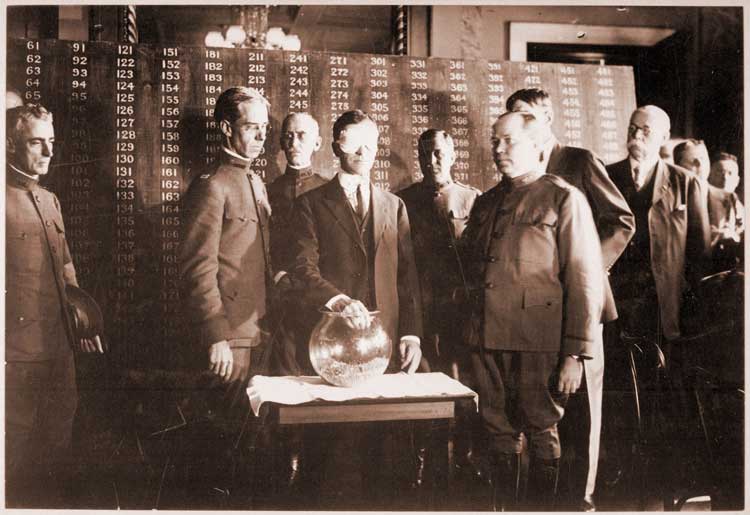

Then, in the summer of 1917, Wilson signed into law the Selective Draft Act of 1917 in order to gather troops to fight Germany in World War I. Many farmers refused to register, seeing the conflict as a rich man’s war.

An elderly farmer named John Spears raised the red Socialist flag over a bluff on the Little River outside Sasakaw on July 27 and called for volunteers to march on Washington.

Seminole County Sheriff Frank Grall and a deputy rode out to investigate. On Aug. 2, they were ambushed in a hail of bullets by five Socialists, barely escaping with their lives.

Munson and Spence held a revival meeting during the night on a sandbar in the South Canadian River to convince farmers that it was time to act. Under the cover of darkness, phone lines into Francis were cut, and the railroad bridges as well as an oil pipeline were destroyed. They met in the morning at the Spear farm where a wagonload of corn and roasted beef waited for them. One of the rebels likened it to a picnic. Nearly a hundred men assembled on the farm.

An informant told Pontotoc County Sheriff Bob Duncan where the rebels were. Duncan led a posse of 25 men on a charge of the Spear farm and captured 10 of the rebels.

During those critical six days following the raid, the Ada Weekly News reported on a series of shootouts and raids in southeast Oklahoma.

Shootouts took place during the following night at Stonewall and Francis. Sixty men were rushed by train to Konawa to prevent rebels from seizing the town. In a shootout nearby, W.T. Cargill, secretary for the rebels, was killed, shot in the back by a posse.

The Ada newspaper recorded that at a rural school south of Spaulding, rebels and a posse clashed Aug. 5, leaving a rebel farmer dead.

A separate shootout took place at a roadblock south of Holdenville, killing a rebel who refused to stop his vehicle. He was riddled with bullets, according to the Ada Weekly News.

A train took 56 captured rebels from Holdenville to McAlester the next day.

Eventually, 450 farmers were arrested and 150 convicted. Munson and Spence were tried for conspiracy and sentenced to prison. They were pardoned by President Warren G. Harding in 1921.

The rebellion allowed both the state and federal governments to clamp down on the Socialists in Oklahoma. By the end of World War I, the Oklahoma Socialist Party was gone, while nationally the Socialist Party was discredited. It was never again to poll double-digit numbers in presidential elections.

The Key Players

Rube Munson: One of the organizers for the Working Class Union, a Socialist organization for tenant farmers, was brought in from out of state by the Industrial Workers of the World organization. He was out on bail for obstructing the 1917 military draft. Munson was the instigator of the idea of marching to Washington. Tried in Enid, he was sentenced to 10 years in Leavenworth Federal Prison.

Homer Spence: One of the organizers for the Working Class Union and out on bail for obstructing the 1917 military draft, he was sentenced to serve 10 years in the Leavenworth Federal Prison.

John “Old Man” Spears: Local county Working Class Union organizer, he raised the red banner of revolution over his farm where tenant farmers were organizing their march on Washington. He received a two-year prison sentence.

Sheriff Frank Grall: A former U.S. Deputy Marshal from Arkansas and police chief of Shawnee, Grall was already famous for being part of a posse that killed a band of train robbers in 1893.

Sheriff Bob Duncan: Originally from Missouri, he had already served nearly a decade as county sheriff when the Green Corn Rebellion took place. He died in 1935.