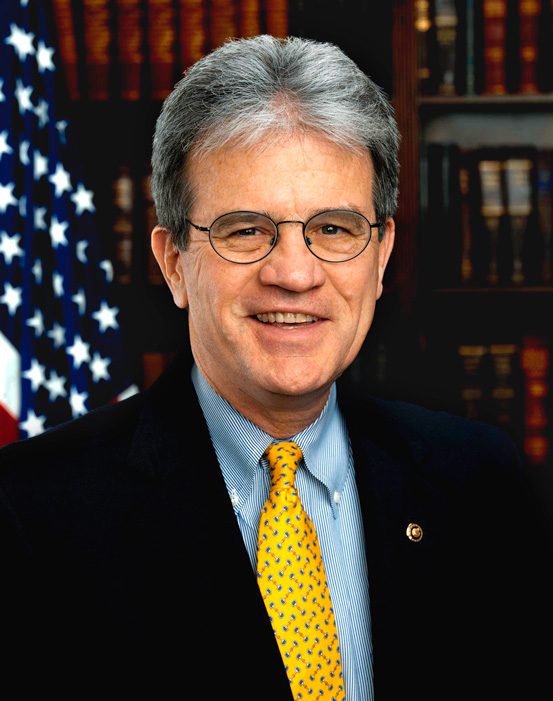

When U.S. Sen. Dr. Tom Coburn left Washington, D.C., in January, he didn’t look back with longing or regrets. He retired with two years left on his term in Congress to return home to Muskogee, his wife, Carolyn, and his career as a family medical doctor.

Regret is a word seldom spoken in Coburn’s vocabulary. He’s an informed straight shooter when he talks about the nation’s Capitol and his time spent there, astutely observing the political climate.

What he did bring back to Oklahoma is a heavy burden about the future of America.

“Washington is a very sick place,” he says.

So ill, in fact, he suggests there’s no real remedy that might turn the country around.

For a man who never intended to be involved in politics, Coburn achieved legendary status, in the United States House of Representatives, serving from 1995 to 2001, and in the U.S. Senate, from 2005 to January 2015.

“I had no early motivation to run for office,” he says. “I just fell into it in the mid-1990s. I had no plans for being a politician or ever being in politics.”

He did hope to make a difference, however.

A Republican fiscal conservative, Coburn was quickly recognized as an elected official who was well aware of how Congress works when he arrived in D.C. He wasn’t interested in getting acclimated to the prevailing climate.

“You can learn the system in Washington in three or four months,” Coburn confides. “That’s not what the politicians want the public to think. I don’t think I ever got comfortable with politics. How do you not speak the truth in such a way that people don’t know it is a lie? In Washington, we chisel the truth, instead of speaking it plainly.”

Family Values

For Coburn, life has always been about living by the old-fashioned values his parents instilled in him – truth, honesty, dependability, accountability. Born March 14, 1948, in Casper, Wyo., to Anita and Orin Coburn, the family moved to Muskogee when Coburn was 2 years old. When Coburn talks about his growing-up years, he remembers an idyllic youth.

“I grew up in a wonderful time,” he remembers. “It was the 1940s and 1950s. We walked to school. We went home for lunch. Our parents were not worried about us. Other parents were always watching us.”

He recalls no mentor or older person he admired beyond his parents and their friends.

“I was busy staying out of trouble and trying not to get caught when I was mischievous,” he says.

“We tend to call ‘mischievous’ an attention deficit syndrome today. Really those kids just have a Y chromosome. All of us have been mischievous at some time in our life, when we have gone way past normal. Children a little out of control need behavior modification more than they need medicine,” he says.

As an obstetrician, Coburn knows something about children. In his practice, he has delivered more than 4,000 babies.

It troubles Coburn that almost 60 percent of today’s children are born out of wedlock.

“Look at what we’re doing,” he says. “We are destroying our families. Government has destroyed the family. Government should make us strong and healthy. But it hasn’t.”

“There’s no shame in this country now. Since Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson, what we’ve done is unwind personal responsibility. Accountability has to be restored and with that public shame,” he insists. “We’ve lost the concept of being humiliated because you decided you don’t want to be responsible. That’s cultural, not political.”

Congressional Record

During his tenure in the U.S. House of Representatives, Coburn wrote and passed far-reaching legislation. These included laws expanding seniors’ health care options, protecting access to home health care in rural areas and allowing Americans access to cheaper medications from Canada and other nations. He also wrote a law intended to prevent the spread of AIDS to infants.

The Wall Street Journal said of that law, “In 10 long years of AIDS politics and funding, this is actually the first legislation to pass in this country that will rescue babies.”

Early in his time in the Senate, Coburn, one of the most conservative members of Congress, became recognized as an irritant – sand in the oyster, chalk screeching on a blackboard. He made colleagues angry or frustrated. His greatest political tool was not in creating cost-cutting legislation or staging a filibuster. Instead, he found loopholes, built roadblocks and put holds on thousands of bills. He was called a “political maverick.”

“I was called ‘Dr. No’ after my first couple of years in the Senate because I would block both Republican and Democrat bills because they were either unconstitutional or duplicative,” Coburn says.

If that created any political paralysis, Coburn says that came not from him, but from the leader of the Senate not allowing any amendments on bills brought to the Senate floor.

“We thought the 200-year history of being able to offer amendments in the greatest deliberative body in the world actually should continue. The Senate leader did not think so because he did not want his members to have to vote on our amendments. The only person I truly upset was Harry Reid. I did a significant amount of bipartisan work with other senators – Chuck Schumer, Joe Lieberman, Barbara Boxer.

“The Senate was never brought to an absolute halt, as the Majority Leader determines what comes to the floor. Most of the time that cloture was not invoked because he would not allow amendments to be offered,” Coburn says.

“I did put holds on thousands of bills, but only because I believed they needed to be debated, or modified, and at least voted on instead of passed in the middle of the night without objections being publicly put forth,” he states. “I put objections publicly written and stopped bills that would not be allowed to be modified or amended. Many bills passed when the authors worked with us on our constitutional concerns.”

Every branch of government was fair game for his frequent calls for conservative reform, especially on rampant, wasteful spending.

“My faith has allowed me to be criticized and not worry about it,” he says. “I get my identity from unearned grace so I can be bold and take criticism and go right on down the road. That is my greatest strength.

“Congress is out of control,” he says. “It spends twice as much money as it needs to. There’s no real accountability in government. When the Internal Revenue Service, the President and the judicial system can do things that are extra judicial, then the bureaucracy and members of Congress aren’t accountable. That’s not a republic. It’s an attempt, but the republic has lost its way.”

In a probing interview on CBS 60 Minutes, which aired Dec. 21, 2014, Coburn called his Senate colleagues “cowards” and told interviewer Lesley Stahl, “Anybody off the streets could do a better job than the senators there now. They make decisions that benefit their career, rather than the country. That’s what makes me sick.”

For all the unflattering names labeling Coburn during his Congressional service, he returned home with an enviable collection of accolades. In 2013, he received the U.S. Senator John Heinz Award for Greatest Public Service by an Elected or Appointed Official, an honor given annually by Jefferson Awards.

Also in 2013, Time Magazine named him one of 100 most influential people in the world. Coburn is still friends with President Barack Obama. Although their philosophies are poles apart, they met as freshmen senators in 2005, wrote legislation together and got it passed. Obama wrote the Time tribute to Coburn and prayed for him at a 2014 prayer breakfast.

In April 2011, Coburn spoke to Bloomberg TV about Obama, saying, “I love the man. I think he’s a neat man. I don’t want him to be President, but I still love him. He is our President. He’s my President. And I disagree with him adamantly on 95 percent of the issues, but that doesn’t mean I can’t have a great relationship. And that’s a model people ought to follow.”

One of Coburn’s greatest worries is “young people today have no idea what the founding principles of this country are. They are not taught this in schools any more.” He also believes any young person who aspires to be elected to public office “should have a career before they enter politics so they will know how life works.”

Cancer Diagnosis and Return Home

After serving more than four years of his second term in the U.S. Senate, Coburn announced on Jan. 16, 2014, he was resigning his office at the end of the year for health reasons. Having survived prostate cancer surgery, colon cancer and melanoma, his prostate cancer has returned. He is currently undergoing chemotherapy treatments.

With his political career behind him, Coburn says his life now “is pretty good when I’m not working. I’m not getting on airplanes very often now. And I’m working my way back into my wife Carolyn’s life.”

Coburn met his wife, Carolyn Denton, in the first grade. Both are Oklahoma State University graduates. Carolyn was Miss Oklahoma 1967 and married Coburn in 1968. When he graduated from OSU in 1970, he went to work for his father, who owned Coburn Optical Industries, based in Colonial Heights, Va. When the company sold in 1978, Coburn used the opportunity to change his career focus from business to medicine, graduating from the University of Oklahoma Medical School in 1983.

The Coburns have three daughters, ages 37, 41 and 44, and seven grandchildren. They live on a 40-acre farm in Muskogee, and he says a perfect day, now, goes something like this: “I get up, study the Bible, have coffee with Carolyn, play golf if the weather is good, read, study, write. I work in my yard, trim trees and mow grass.”

Some days are devoted to chemotherapy treatments for his prostate cancer.

For the past 15 years, Coburn has taught a men’s Sunday School class at Muskogee’s First Baptist Church. He came home from D.C., every weekend to be with his family and teach the class.

“I’ve had a wonderful group of 75- and 80-year-old men. I’ve learned a lot from them through the years. They have taught me patience and that I’m never too old to grow and learn. What I’ve seen more than anything is how their lives have been totally changed through their faith,” Coburn reflects. “In the past 15 years, we have jumped around in the New Testament. We are almost completing it.”

His Legacy

“I shouldn’t be remembered,” he says. “No politician should ever be remembered. We should remember the founding principles of our country. We should not remember politicians.

“In my opinion, there’s only been one great president, in my lifetime. That was Ronald Reagan. He actually knew what he believed. He wasn’t afraid to speak it. If it wasn’t politically correct, he didn’t care. It was real leadership.”

While Coburn is bold in his political viewpoints, he’s humble about his achievements.