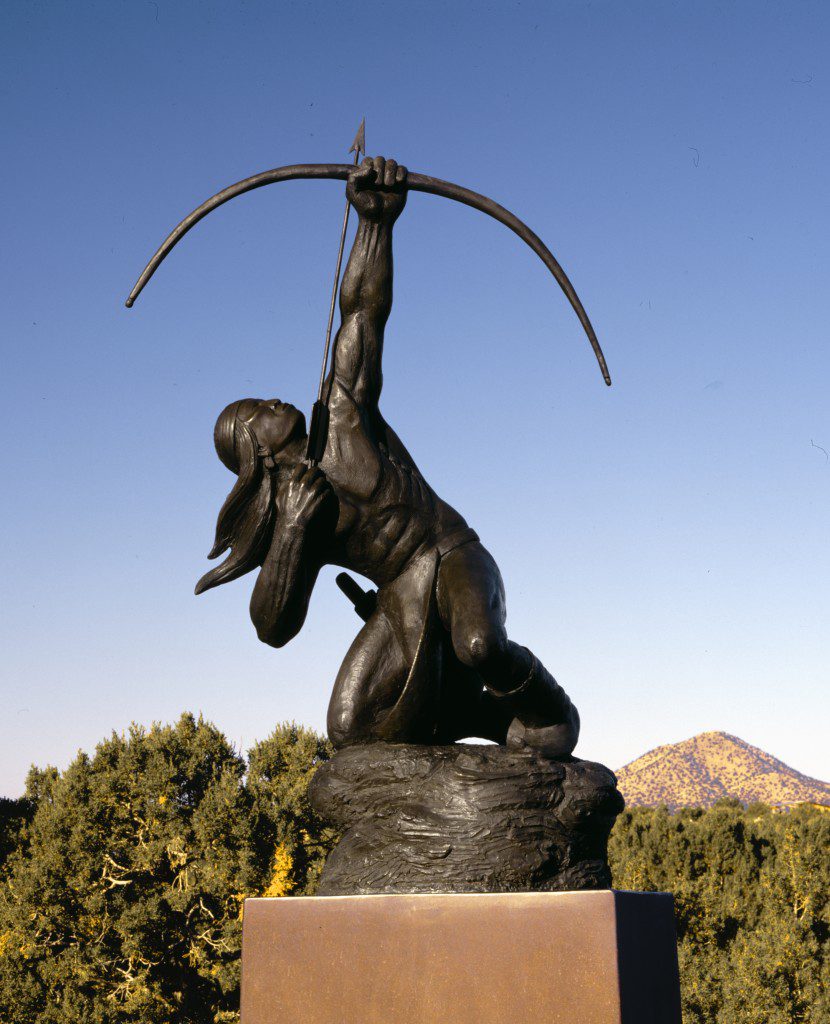

Photo courtesy Allan Houser Inc.

Many Journeys

In 1948, Houser was chosen for another commission from the interior department. The new commission, however, was different. It was not for another mural in a government office; this time, he was asked to produce a sculpture for the Haskell Indian School, now Haskell Indian Nations University, in Lawrence, Kan. Haskell had been given an eight-foot block of Italian Carrara marble, Rettig says, and both Houser and the department were concerned that he had never done much sculpture before, certainly nothing on this scale.

“He didn’t have any tools, he didn’t know how to carve stone,” Rettig says. “He told me the first thing he did (was) he showed up out there in Lawrence and went to the head stonemaker and asked him what kind of tools and chisels he could borrow or find.”

Houser began by taking a steam jackhammer to the marble. Eight months later, he finished Comrade in Mourning, which became one of his most famous sculptures and officially made him the first contemporary American Indian fine art sculptor. Years later, that first piece would be featured in a 2004 retrospective exhibition art show opening the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C.

There was a lot of interest in American Indian art in the 1920s to 1940s, Rushing says, and Houser was fortunate to catch the end of that period. But the 1950s saw the market for indigenous art and craft wane, and opportunities to show work declined. The trend continued into the 1960s. During that time, Houser found work illustrating books for children and young readers. He also began teaching at the new Institute of American Indian Art in Santa Fe.

Between preparing for classes, teaching and family life, Houser made studio time to experiment and make art. Whereas early in his career he made watercolor and wash paintings using the imagery of the past, Houser now began looking at the forms of men, women and children and of the spaces around them. The lines were simplified, cleaner but had more weight, bearing and meaning.

To his son – artist Phillip Haozous – Houser lived in another world the younger couldn’t understand as a child. It would take years before he could see his father’s intent.

“He was a native artist who refused to be limited by traditional things, was interested in the history of modern art, was interested in the art of the American West,” Haozous says. “He determined very much to be his own man as an artist, and that was inspiration to a couple of generations of younger artists who saw him as a father figure.”

Haozous, president and CEO of Allan Houser Inc., says he and his four brothers, as they grew, had to find their own paths as artists, and Houser encouraged them.

“He was so occupied in his art, you know, we weren’t real, real close to him until, as we got older, he began to accept us a little more. But he was … in a place in his life where he was really moving forward, and we were kind of stumbling around in the dark,” Haozous says.

Three brothers – Phillip Haozous, Bob Haozous and Roy Houser – went into the military. When he was released from duty, Phillip Haozous began working with his father in the studio, and they became closer. Like his brother, artist Bob Haozous took back their family’s Apache name and explored art and its boundaries.

“My father was no less influenced by the rules of art-making than I am. He was told that being Indian was a historic identity and no longer valid, and (that) he should produce artwork that was market focused,” Bob Haozous says. “He immediately broke away from that simply because he was drawn to his natural creativity rather than the market needs, and that followed him his whole life.”