The Transcendence

Houser continued to paint through the 1970s, but when he retired from teaching in 1975 and took to his studio full-time, he was ready to wrest his ideas out of surfaces he had yet to fully explore. Painting was no longer the focus, and he put his energy into sculpting and, later, drawing.

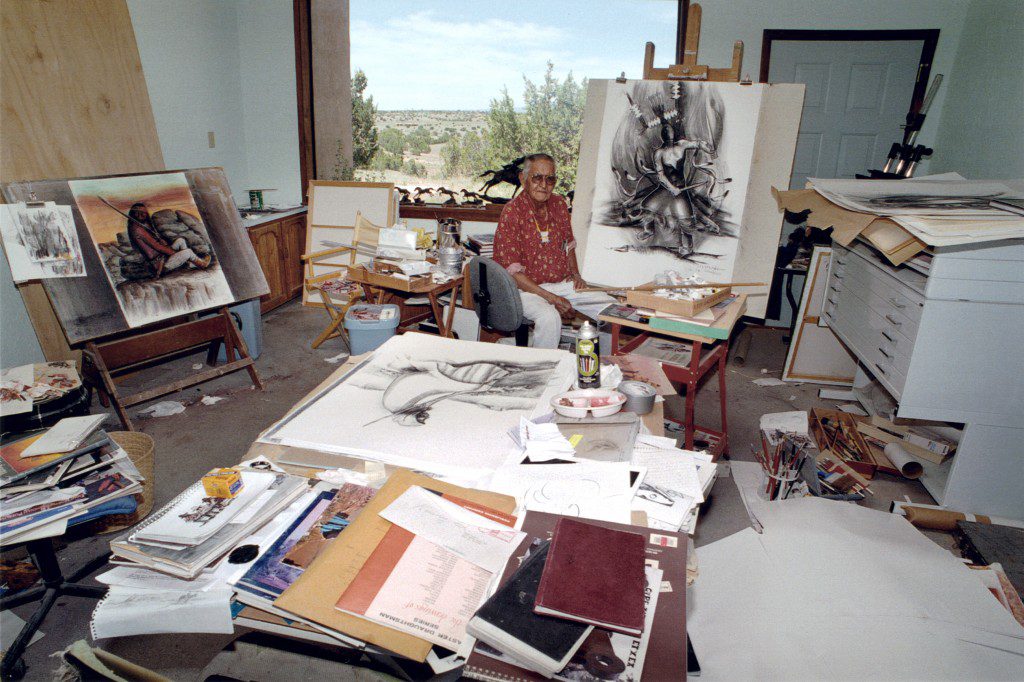

In the 19 years between his retirement and death, Houser created 90 percent of his sculptures, about 850 pieces. He constantly sketched out designs, leaving behind 239 sketchbooks crammed with drawings on every page. He then created a series of large drawings, preferring the spontaneity of sketching and drawing to the extensive planning involved in painting, Rettig says.

During that time his work received more attention from the public than he’d ever known, and his art was sought by institutions and collectors from around the world.

“He was one of those native artists who transcended the category of ‘Indian’ or ‘native’ and was recognized at the national level and even international level as a great artist, regardless of his ethnic background,” Burke says.

When Houser worked in his studio, it was “a peaceful place to be,” Phillip Haozous says. “He seemed always to be very calm, never excited, never bothered by anything. He just sat in his studio and just peacefully went about his work. I’d walk in, and then he’d just look over at me and smile. And then we’d talk a little, and I’d watch him work. It was very relaxing for me to see him at play.”

Rettig remembers observing Houser sketching and the intensity he put into it.

“With drawing, it was so beautiful to watch,” Rettig says. “He’d drawn for so many years … that he made the most complex things look effortless. He’d take a piece of charcoal, and by just one gesture, he could create a line that had so much nuance that he could define motion, he could define the fold in fabric, just never taking the charcoal off the paper.”

In the last four years of his life, Houser created about 250 large charcoal and pastel drawings. While his design transitioned from representational to more modern and contemporary, Houser continued to be inspired by the Apache people and other tribes as subjects for his work. The subjects grounded him as his spirit explored the lines and directions of contemporary art beyond the American Southwest.

“He broke away, but he was always with Indian people. He always maintained a very strong, indigenous sense of his identity and personality,” Bob Haozous says.

Houser never forgot the history of his family and the Chiricahua, but like many from the generations before him, he didn’t speak of it. He used it to fuel his art, including a drawing of two young men in chains.

“One presumes that they are, in fact, at Fort Sill, but even in their imprisonment, they sit upright,” Rushing says. “They’re very handsome, they gaze out toward the future without fear. It’s a remarkable drawing about survival.”

Houser not only survived, but seemed to be at peace in his life and work.

“His mother was very Christian,” Bob Haozous says, “and once, she asked him why he didn’t go to church, and he told her, ‘All I need to do is take a walk.’”

Houser died Aug. 22, 1994.

Phillip Haozous says his father was never one to explain his work, but that was part of what made Houser unique not only to American Indian art but art in general. He wanted to be a good artist, one whose work left an impression and room for the viewer to inwardly explore.

“Even in the abstract and modern pieces, it’s up to everyone’s own impression what they get out of the piece,” says Phillip Haozous.

Today, the Houser family compound – a multiacre property with a sculpture garden, studios, gallery space and living quarters south of Santa Fe – welcomes tourists to view Houser’s work and favorite scenery.

“He had said he wanted to be known as one of the best ever in the world,” Phillip Haozous says, “and he was pleased with what he had done, but he was kind of sad that he had to leave … Unto the end, he was inspiring.”