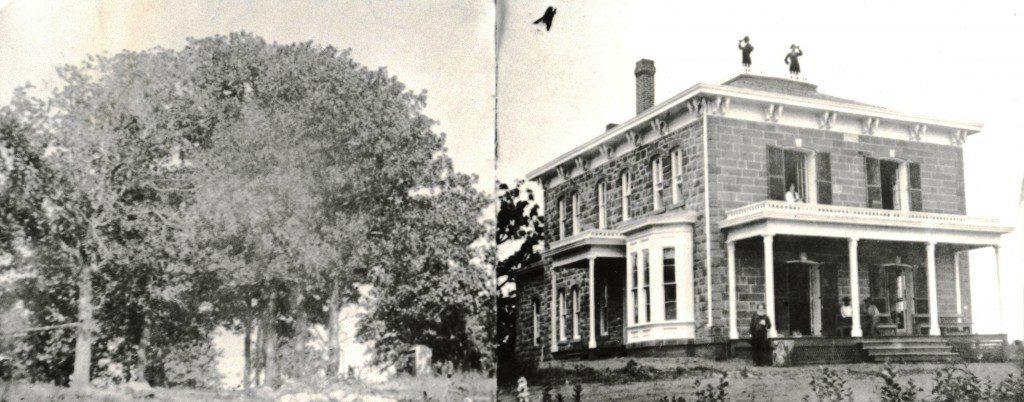

[dropcap]The[/dropcap] Five Civilized Tribes Museum stands tall atop Agency Hill at Honor Heights Park in Muskogee. The vintage 1870s sandstone building is like a proud sentinel, overlooking this celebrated park.

“It is amazing the building is still standing,” says Sean Barney, the museum’s new executive director, who, with the museum, is dedicated to sharing the culture of the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee (Creek) and Seminole tribes during the 50th year of the museum’s history.

Barney assumed the director’s post two months ago and loves reflecting on the museum’s history. Originally the Union Agency Headquarters, it was here tribal citizens received their land allotments.

When trains began traveling through Muskogee, citizens walked six miles from the downtown depot to Honor Heights to conduct business. The distance caused the Agency Office to relocate, and the building sat empty for 37 years.

After that time, it hosted a patchwork of colorful occupants, as varied as the rainbow hues of a Seminole ribbon dress. It was a school and Creek Freedmen orphanage. Dances were held here during World War II. The American Legion called it home for several decades. For four years, Minnie Posey, wife of noted Creek poet Alexander Posey, presided over a popular tea room.

[pullquote]Land and lease restrictions prohibit museum expansion, but that doesn’t keep me from thinking big. For the space we have, our private collection is amazing.”[/pullquote]September 1951 was a turning point for the building, when the women of the Da-Co-Tah Indian Club considered establishing a museum. Renovations began August 15, 1955, 80 years to the day after the first cornerstone was laid in the building. During 1964 and 1965, the women’s club raised $94,000 for its restoration.

“It took an act of Congress to have the 5 1/2 acres and the Agency building’s ownership given to the City of Muskogee,” Barney notes. The museum was incorporated Nov. 19, 1965. Ed Edmondson, then a U.S. House of Representatives member, authored House Bill 3867, giving the building back to the City of Muskogee from the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The museum opened April 16, 1966; Will Rogers Jr. was keynote speaker. Until then, Barney explains, “there was no place that encouraged Five Tribes citizens to preserve their heritage.”

For Barney, the 50th anniversary is a year-long event. The April 16 celebration includes the annual Art Under the Oaks outdoor sale, a tribal encampment and play, storytelling, craft demonstrations and a movie, The Dawes Commission.

A resident of Muskogee for 10 years, Barney has been a museum member for two years, serving on the 2015 Museum Board, before assuming the leadership position. His varied background includes spending his youth in Europe, where his father was stationed with the U.S. Air Force. In the 1970s, the family returned to the U.S., living in Washington, Montana, New Mexico and Oklahoma.

As a ninth grader, he studied Oklahoma history and its Native American influence. Now Barney is discovering new facets of the Native American culture. His small, second floor office was once a superintendent’s bedroom.

He remembers well his first impression of the Five Tribes Museum.

“I thought it had great potential but was too small,” he says. “Land and lease restrictions prohibit museum expansion, but that doesn’t keep me from thinking big. For the space we have, our private collection is amazing.”

This year, Barney is focusing on the art/culture of each tribe, drawing work from museum archives. Creek artists include Acee Blue Eagle, Joan Hill, Lee Joshua, Jon Mark Tiger, Jimmie Fife, Johnny, Jerome and Dana Tiger and Enoch Kelly Haney, known for his Oklahoma Guardian sculpture atop the Oklahoma State Capitol.

A Haney painting hangs behind Barney’s desk. The central figure appears to serve as Barney’s guardian in his new role.

Valjean Hessing and Gwen Lester Coleman are representing Choctaw artists. Cherokees include Troy Anderson, Joan Hill, Donald Vann and Bill Rabbit. Representing Seminoles are Mike Daniel, Lee Joshua and Benjamin Harjo. Mike Larsen’s art honors Chickasaws.

While planning future public events is an integral facet of Barney’s museum management, he’s also focusing on the museum’s five-year strategic plan. It includes using the latest technological advances to be successful in the competitive museum marketplace across the nation.

Digitalization is in progress for every museum item – art, artifacts, photos, documents, correspondence. “Most museums set this as a 20-year goal,” he notes. “We intend to complete it in five years.” Digitalization allows other museums and libraries to access and borrow from the museum’s holdings.

Barney considers the museum a safe harbor for the five tribes’ history. He enjoys exploring the museum’s vast archives, which bulge with more treasures than can ever be displayed.

“It’s a shame the public will never see many of these things,” Barney says. “But if someone suggested we build a new, larger museum I would now oppose it. I’m a sucker for old buildings and their history.

“We are known statewide as a leader in Native American art and history,” he continues. “There is more here than meets the eye. I’m lucky to be doing what I am.”