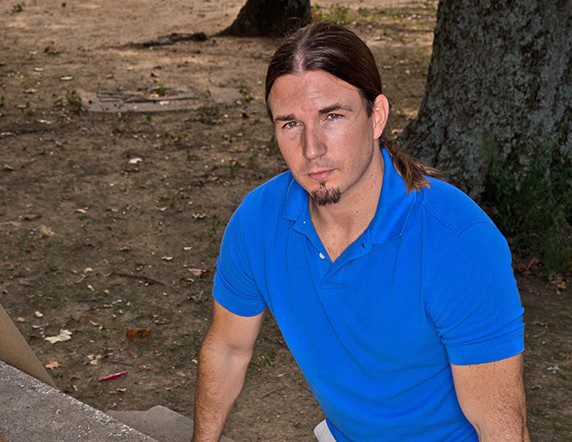

While most cartographers today map our ever-changing world, Aaron Carapella maps history to change perspectives.

He searches for the truth of American Indian tribes, carefully placing their original names on a borderless map to identify lands each called home before European settlers arrived. “This was a pivotal moment in my life,” he says. [pullquote]“I learned from this experience that hands-on activism is appropriate at times, but I also believe that introducing curriculum to the educational system is also part of the puzzle.”[/pullquote]

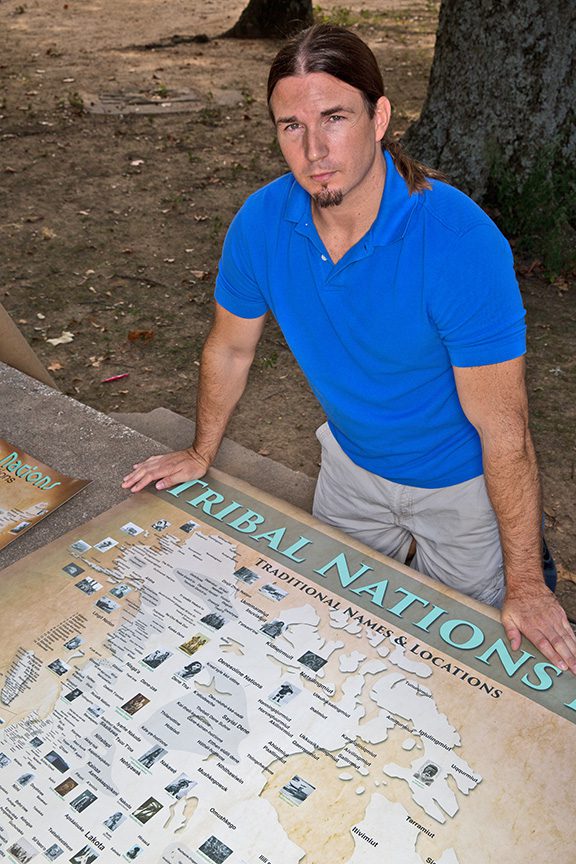

“They are living maps, which means they are not set in a static year,” says Carapella. “I wanted these maps to convey what lands were held by whom at the time of contact with outsiders to show which lands each tribe fought to maintain and which ones many of them lost or were moved off of.”

Though he now lives in Stigler, Okla., Carapella’s map-making inspiration came during his childhood spent in California.

“I looked for a map of tribes to put in my room, but only came across ones that had a few dozen tribes on them,” says Carapella, who is of Cherokee descent, but is not enrolled with a tribe. “I already knew at that time that there were hundreds of tribes because I spent most of my free time reading books on Native American history.”

At age 18, he joined the American Indian Movement. As he worked to remove offensive mascots from local schools and protect sacred areas, Carapella says he unearthed a lack of understanding by many Americans.

“This was a pivotal moment in my life,” he says. “I learned from this experience that hands-on activism is appropriate at times, but I also believe that introducing curriculum to the educational system is also part of the puzzle.”

So, for the next 14 years, he intermittently worked on his first tribal map, looking for information wherever his travels took him – including around 250 tribal reservations.

“I have always made it a point to visit tribal museums and other historical locations, speaking with whoever I could find that would give me a sense of local tribal history and traditional names,” says Carapella.

As a self-taught cartographer, his drive to develop the skill came from a desire to resurrect the identities that were being lost in translation and time. According to Carapella, only three percent of commonly known tribal names are actually the traditional names.

“I have had many people say that these maps taught them the correct name of their people, and that might be one small step towards maintaining identity,” he says.

The maps have value for every citizen, though.

“They serve as a reminder to non-natives that these lands were homelands, occupied by tens of millions of people since the dawn of time, and also that these peoples still survive today,” Carapella says.